We are anarchists.

Anarchism is a philosophy which, over the years, has often been seriously misunderstood, thanks largely to the efforts of its enemies. But the situation seems worse than ever today, in that even those who call themselves anarchists sometimes lack a clear understanding of what it involves. Sometimes they accept the comic-book version of anarchism presented to us by the mainstream media and so help perpetuate that parody. Sometimes they undermine the whole sense of anarchism by trying to combine it with a political philosophy with which it is entirely incompatible, such as capitalism, liberalism, postmodernism, Marxism, nationalism or the politics of “racial” identity.

By real anarchism, we mean an anarchist vision unblurred by a confusion of other ideas and influences, an anarchist point of view which is strong and coherent because it is built on the foundation stone of anarchist philosophy. Anarchism, as a political movement, is doomed to disintegrate and disappear if it fails to reconnect itself to the roots of its own world-view.

Anarchy comes from the Greek terms arkh meaning “ruler” and an- meaning “without”: it therefore means a society without rulers. An anarchist is someone who thinks we should live without rulers and who tries to push society in that direction. Note that an anarchist isn’t just someone who thinks we could possibly live without rulers, in certain circumstances and if certain conditions were met, but someone who thinks it preferable to live without rulers.

The obvious question which springs to mind is why do anarchists think it would be better to live in a society without rulers, without government? After all, most of us have been brought up to believe that a state, the rule of law and so on are necessary for our well-being and protection. There may be arguments about how much power the state should have, or how it should use that power, but there is no general question about the need for some kind of authority in charge of our society. People assume that without a government, human society would fall apart into chaos, with everyone trampling over each other in a brutal “dog-eat-dog” world. The word “anarchy” is often used in this way by non-anarchists. They talk about a fear that we could “descend into anarchy”.

From this perspective, the anarchist point of view doesn’t make any sense at all. One common conclusion is that anarchists must be hopelessly naïve to believe that it could be possible to do away with authority without disastrous consequences. Another reaction is that anarchists must be destructive-minded and violent people, who actively want society to slip into a nightmarish condition of chaos. In fact, these two depictions of anarchists are used pretty much interchangeably by our enemies, particularly in the mainstream media, depending on the needs of the moment. One day anarchists are bunch of woolly-minded idealists, completely detached from “the real world”, foolishly clinging to a childish cloud-cuckoo fantasy of stateless society. The next day they are a sinister and violent gang of sociopaths, plotting underground to wreak havoc and destroy everything that is good in society.

Behind all this misunderstanding and misrepresentation of the anarchist position lies the important question of how we regard human nature. If you believe that humans are naturally selfish, greedy and violent, then you will argue that they need the structure of a state to control them. If you believe that there is no such thing as human nature, and that we are entirely shaped by the environment in which we grow up, then you will be keen to ensure that the correct environment is provided and may well look to some kind of state to ensure this happens.

But what if you believe that humans have a natural tendency for co-operation rather than for competition, for mutual aid rather than for mutual robbery? This is the anarchist point of view, most famously set out by the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin in his 1902 masterpiece Mutual Aid. In this case, you obviously do not believe that a state is necessary to hold society together, as this is something that happens naturally from within, because of this tendency for co-operation.

This difference between the statist and anarchist outlooks is fundamental. It is the point where anarchism diverges from all other political philosophies. So it is crucial to understand why Kropotkin and other anarchists have this particular view of human nature. Kropotkin made it quite clear in Mutual Aid, and elsewhere, that it is not just human nature he is describing. All animals show the same tendency to co-operate, simply because it makes sense. That is how species, including the human species, survive and flourish – by working together and looking out for each others’ interests. He makes it clear that this is only a tendency he is describing. There are plenty of instances of competition in nature, as well in human society. Anarchists do not suggest that a future anarchist society would never involve any conflict between individuals or groups. But the overall pattern remains one of co-operation.

This potential and natural tendency for co-operation and mutual aid is based on our belonging to the natural world, where co-operation remains intact as the general rule of life. It is a continuation of nature within humanity, the extension of the organic structure of nature into the realm of human affairs. A human society without a state can hold itself together because that is what it had evolved to do, before the modern era of hierarchies warped our ways of living.

So-called anarchist thinking in recent decades has been overly influenced by other philosophical ideas which do not share its roots. It is fashionable in some circles to reject the idea of “nature”, particularly when applied to human beings. It is wrongly seen as being some kind of restriction applied to individuals from the outside, an attempt to make them conform to someone else’s model. This hasn’t been helped by the right-wing misuse of the words “natural” and “unnatural” to describe behaviour or ways of being that are considered acceptable or unacceptable by certain groups. This has nothing to do with actual nature, which is simply the living world of which we are part.

Nature is at the heart of real anarchist thinking. The idea of a natural state of freedom that has been stolen from us by states, churches and other forms of domination underlies the whole anarchist tradition. Time and time again anarchists write of removing the constraints of the state, so that we can organise ourselves into co-operative societies where we will always have the potential to flourish.

For most people today, the existence of a state is accepted as something necessary for the general welfare of humanity. But what does the state represent for anarchists? If human society naturally functions well on its own, and then something comes along which interferes with that natural functioning, then that thing is a problem. Yes, the state is unnecessary, but it’s even worse than that. It is actually stopping us from living how we should be living. The state is a positive menace to human well-being.

Comparisons are sometimes made between anarchism and the ancient Chinese philosophy of Taoism. Taoism describes a natural flow to the world which can be blocked and disrupted by any attempts to control it, even well-meaning ones.

For those who see anarchy as being a natural and desirable condition of humankind, all kinds of authority are regarded as both unnatural and undesirable. This is the basis of the anarchist position. While those in power regard anarchists as wanting to turn their world upside down, anarchists regard the current world as already being upside down and want to put it back the right way again, how it’s meant to be.

Seen from the anarchist point of view (from the right way up), all the structures of our current society take on a different appearance. They are revealed as ways of keeping us enslaved and concealing from us the truth about our predicament. Here are some examples.

The state. Anarchists regard the state as an appalling imposition. A group of powerful people declare themselves to have some kind of right to authority, tell the people they need that authority, and then force people to obey them. This is unacceptable.

Property. The powerful people who run the state also claim to “own” parts of the surface of the Earth and exclude others from these areas.

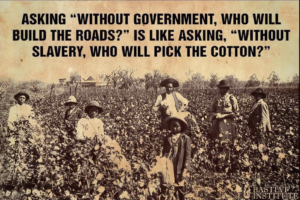

The law. This is the way that all the theft and domination is justified, disguised and imposed. The law replaces the principle of “right” and “wrong” with narrow definitions of “legal” and “illegal” suiting the interests of those who run the state, possess the wealth and write the laws.

The police. They are the physical means by which the powerful people who run the state violently enforce obedience to their system.

The “nation”. The concept of a “nation” is a false one, designed to give legitimacy to the existence of states controlling particular territories. Obviously there are fluid cultural and linguistic identities across the world, which should be defended from statist imperialism and centralisation, but anarchists reject any idea that these identities are fixed or that humans can be defined by national or racial labels.

“Democracy”. To hide the reality behind their theft and domination, the powerful people behind the state have constructed an elaborate façade of so-called “democracy” to persuade the dispossessed majority that they do, in fact, have a say in the running of society. The usefulness of the illusion of “democracy” is to head off the need for constant violent repression of the public.

The main aim of the powerful people behind the state has always been to increase their own wealth and power at the expense of everyone else. They disguise this aim by describing it as “progress”, “development” or “economic growth”.

In order to boost their own wealth, the ruling class have stolen from the rest of humanity the ability to live freely off the natural fruits of the land and trapped us into a complex system of enslavement based on money. The basic idea is that you either become a slave to their system, or you starve. To encourage voluntary submission, we have been taught to think that any kind of paid employment has a positive value, whatever the work involves. The accumulation of money and possessions is likewise presented as praiseworthy in itself, and confers social status.

The increase in the wealth of the ruling class – or “economic growth” as they call it – is presented as an unchallengeable priority, justifying unending and ever-increasing exploitation of life in all its forms – human, animal and our natural environment.

Anarchists reject this rhetoric, and everything that goes along with it. We have our own set of values which have got nothing to do with the fake and self-serving “values” of the world of money.

Ethics form an important part of the anarchist vision. There is already an ethical dimension in the basic idea of a co-operative way of life founded on mutual aid. But real anarchists extend this further in seeing a sense of values which naturally goes hand in hand with the idea of a self-governing and organic anarchist society. These values provide an ethical structure for this society; they are the fabric that make it possible and hold it together on a physical level. This basic concept has been shared by many cultures in human history. It is the Chinese Tao, it is the Indian idea of dharma or cosmic order, or the indigenous South American sumak kawsay or “right way of living”.

This anarchist dharma is key to the superiority of anarchist society. As well as naturally having a tendency to co-operate, for survival and well-being, humans have a tendency to be guided by certain values which help build harmonious and sustainable societies. Respect for each other, respect for other creatures, for trees, plants and rivers. These values are commonplace amongst us but are not allowed to come to the fore and guide the direction of our societies, because of all the false structures imposed upon us.

Freeing humanity from the yoke of state control and enslavement would also free us to live according to values coming naturally to us, rather than being forced to obey the laws imposed on us by the slave-owning minority.

People new to anarchist ideas often misunderstand the role of the individual in anarchist philosophy. The emphasis on individual freedom leads some to imagine that anarchism is little more than an extreme form of individualism, a mere libertarianism which could theoretically be coupled with liberalism or capitalism. However, this interpretation neglects the strong social aspect of anarchism, its emphasis on our innate tendency towards co-operation and mutual aid.

Anarchism rejects the idea that there is an inherent clash of interests between the individual and the community, which has to be resolved by some kind of social contract or compromise. Instead, it understands that the individual human’s sense of belonging to a wider community is a natural one, if allowed to flourish. We do not need a state (whether capitalist or communist) to artificially impose that belonging and loyalty on us – indeed, trying to do so is more likely to destroy affinity with wider society.

Because anarchists maintain that humanity has a natural tendency towards co-operation, we trust people to organise themselves, rather than wanting to force them to behave in the ways that we see fit by means of laws, police and so on. For anarchists, the idea of complete freedom for all individuals is not something to be feared, because we recognise that, in the long run, individuals will act in the interests of the communities of which, after all, they are part. For the minority who use the structures of the current system to dispossess and exploit the majority, complete freedom is indeed to be feared – as a threat to their own privileged status.

Freedom of the individual is, for anarchists, necessary for the freedom of the community. A society cannot be considered free if its members are not free. An individual cannot be considered free if they are not free to act according to their own conscience and their own values. Those values are found deep within each of us. But, since each of us is also part of the human species, these are shared human values. When we search in our hearts for what is right and wrong, just and unjust, we are searching within the collective culture, the collective thinking, of humankind.

And embedded within that collective human culture is the idea of dharma, or Tao, or natural harmony, the sense of rightness by which human society can guide itself. When that sense of rightness has been obscured by all the false representations of contemporary society, it is the role of anarchists to bring it back to the fore.

Since anarchists demand complete freedom for all individuals, it goes without saying that we also recognise a complete equality of worth in all. The labels attached to people by current society, denoting their social or “national” or “racial” status, have no meaning for anarchists, who see only fellow human beings with a right to define themselves as they see fit and to be treated with respect by others.

We know that many in society today are subject to discrimination and oppression in ways that are not always seen, or regarded as significant, by others who do not undergo the same experiences. And we know that it is important to always remain aware of this. However, anarchists do not define ourselves in terms of our oppression, or accept the role of victim. We prefer to fight back, focusing not on the differences between us but on what we all have in common.

Anarchism is not a narrow dogma and emerges in many different forms. Sometimes it can embrace struggles which may not be anarchist themselves, but are wholly compatible with anarchism. Anti-fascism is a good example of this. Not all anti-fascism is necessarily anarchist, but all anarchism is necessarily anti-fascist, as fascism is entirely incompatible with anarchism. Likewise, while class struggle does not have to be specifically anarchist, class struggle is very much part of the anarchist struggle – specifically the struggle to abolish the whole economic system in which humans are ranked in “classes”.

It has become fashionable to dismiss any idea of revolution as naïve. It is argued either that it is impossible, or that it will merely lead to new forms of oppression. But for anarchists, real naïvety lies in imagining that real change can be brought about without revolution. This is not revolution in the state-communist sense of a transfer of power to a new ruling elite. Anarchism aims at nothing less than the permanent destruction of the state and all the layers of authority it uses to enslave us.

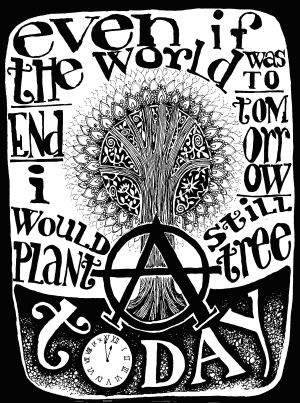

While short-term social gains are not to be sniffed at, they are always to be seen for what they are. Without the demolition of all the structures of current system (law, work, patriarchy, borders, etc.) the structure of enslavement will remain intact and will, in time, reassert control. Real anarchists refuse to abandon the call for revolution, because we know that it is our only hope. Moreover, the myth of revolution, the dream of the complete destruction of the current system, is something that can galvanise action, that can capture people’s imagination and create powerful energies. One thing is for sure, and that is nothing will ever change if we all give up believing that change is even possible.

The anarchist view of the individual comes into play again when the question of revolution comes up. For us, the freedom of the individual is always combined with the responsibility to use that freedom in the general communal interest. In times of social harmony (i.e. anarchy), this would involve protecting the dharma of a stable and happy community. But in times like ours, where the world is upside down, the responsibility lies elsewhere.

Instead, say anarchists, individuals must find within themselves the strength to fight against the oppressive system in whatever way they can. This is partly a question of asserting own individuality through our dissent from the status quo and our adherence to our own set of values. But, of course, we are also acting in the interests of the wider human community – as our values demand. Any anarchist who is true to themself has no choice but to act.

This courage to destroy injustice, tyranny and domination in all its forms is sometimes mistaken for negativity. But in fact anarchism has the deeply positive aim of sweeping away an existing negativity blocking human well-being and happiness. Anarchism is the spirit of life reasserting itself against oppression.