In assocation with Winter Oak, we have produced an expanded version of Crow Qu’appelle’s booklet of conversations with Paul Cudenec, featuring this interview, not originally included in the collection. We have also taken the opportunity to change the title, which is now There Is Nothing More Powerful Than An Idea Whose Time Has Come: The New Anarchism. Thanks to Jordan Henderson for the cover!

One of the things that I found striking over the course of the COVID psy-op was the extent to which people in First World countries seemed terrified of having unpopular opinions. This was not limited to liberals or to leftists, but it did seem more pronounced among this demographic.

It was extremely disconcerting to me. I have been fascinated by psychology for as long as I can remember, and I thought that I understood the human mind fairly well. Clearly, I was wrong, as I never in a million years would have thought that it would be possible to get such insane mileage out of one flimsy-ass lie.

After I got over the shock, and started trying to understand what the fuck was going on, I decided that the likeliest explanation was that digital technology was to blame, and that social media apps were programming the population by hacking the brain’s reward mechanism circuitry, which is mediated through dopamine.

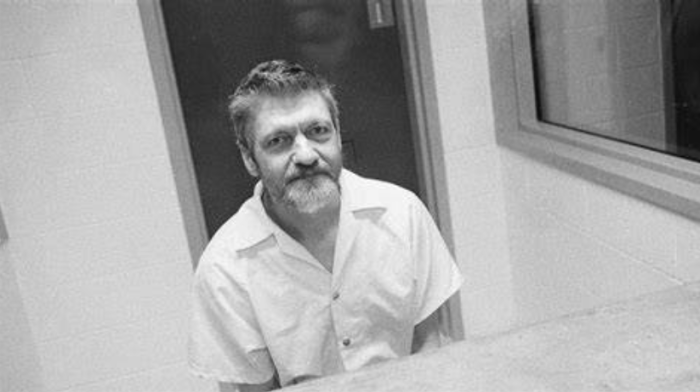

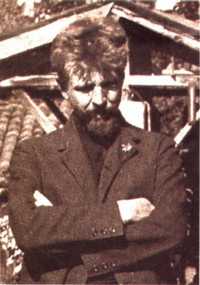

More recently, I came across a potential explanation for this behaviour in the writing of Ted Kaczynski, who dedicated a lengthy segment of his manifesto to diagnosing the problems of leftist psychology. In my opinion, he hits the nail on the head with his concept of over-socialization.

He writes: “Psychologists use the term ‘socialization’ to designate the process by which children are trained to think and act as society demands. A person is said to be well socialized if he believes in and obeys the moral code of his society and fits in well as a functioning part of that society”.

He goes on to say: “Some people are so highly socialized that the attempt to think, feel and act morally imposes a severe burden on them. In order to avoid feelings of guilt, they continually have to deceive themselves about their own motives and find moral explanations for feelings and actions that in reality have a non-moral origin. We use the term ‘oversocialized’ to describe such people”.

He then concludes: “Oversocialization can lead to low self-esteem, a sense of powerlessness, defeatism, guilt, etc. One of the most important means by which our society socializes children is by making them feel ashamed of behavior or speech that is contrary to society’s expectations. If this is overdone, or if a particular child is especially susceptible to such feelings, he ends by feeling ashamed of HIMSELF”.

It seems to me that the adoption of smart phones and social media apps has accelerated the trend of over-socialization, and that this concept can help us understand the phenomenon of wokeness, among other things.

The fact that many people now struggle to muster up the courage to have their own opinions does not exactly inspire confidence that a bold and mighty revolutionary wave is about to break forth. Rather, it suggests that much of the necessary work involves some kind of psychotherapy.

And at that point, we’re leaving what is generally considered the political domain and moving into the realm of self improvement, of healing, or of spiritual discovery.

I think that this is something that makes a lot of people uncomfortable, including myself, as it could easily justify a retreat from real political struggle towards inward-looking self-absorption.

On the other hand, I think that an understanding of both individual and group psychology is important for any mature political movement.

Amongst contemporary political thinkers, Paul Cudenec stands out for the holistic nature of his worldview, which weaves together strands of many different philosophical traditions. Personally, I think that it is for this reason that his thought has held up through the COVID nightmare, whereas that of many more conventional intellectuals like Noam Chomsky did not.

In my opinion, the idea of revolution that many people have is juvenile, for the simple reason that it is rooted in “Us-Versus-Them” type thinking, which is the main problem of politics to begin with.

As the great Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn said: “If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

The line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of …

This is why I agree so profoundly with Derrick Broze when he says “Revolution without healing is a recipe for disaster”. I hope that this saying becomes an axiom, and I don’t think that it can be repeated often enough. Tens of millions of people died as a direct result of the revolutions of the 20th century, and there is no excuse for not learning from this history.

As the anarcho-punk legends Crass put it in their great anti-Marxist anthem:

“Nothing’s really changed for all the death that their ideas created.

It’s just the same fascistic games but the rules aren’t clearly stated

Nothing’s really different, ’cause all government’s the same

They can call it freedom, but slavery’s the game”.

Hurt people hurt people. We all know this. This is why the revolutionary project, if we are to speak meaningfully about such a thing, must include a dimension which concerns itself with the well-being of the soul. And this is the domain not only of religion, but also of psychology, which was created largely to fill the void created by the death of God.

It therefore behooves us to study the mind before we go out trying to change the world. And the place to begin, of course, is with one’s own mind – with the pursuit of self-realization, which is the impetus for all that which can be aptly deemed heroic.

So, without further ado, I present my latest interview with Paul Cudenec, who I believe is showing us that some of kind of ideological syncretism is the answer to the current crisis of meaning afflicting our world.

CROW: One thing that I like about your writing is the importance that you place upon psychology, specifically the search for self-actualization.

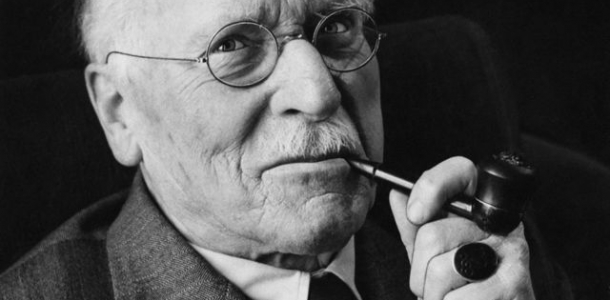

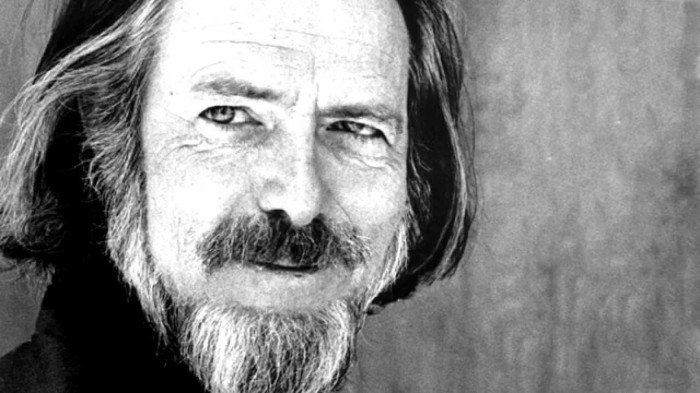

In your work, you make frequent references to psychologists such as Joseph Campbell, Carl Jung, Otto Gross, and Alan Watts. To me, it makes a lot of sense to mesh the political aspirations of anarchism with the spiritual aspirations of depth psychology.

To my mind, the two mesh well. It makes a lot of sense to want people to be free if you believe that freedom is a necessary precondition for them to become the best versions of themselves that they could possibly be.

Could you speak a bit about how you see the connection between political struggle, personal development, and psychology?

PAUL: That’s a big question! To understand my position on this, it’s important to understand that I see the entire universe as one living and intelligent being. Individuals, including humans, are therefore really temporary forms taken by the whole as part of its “being alive”. Because we have specific roles to play within this whole, we are born with certain innate impulses, which at the most basic level we might call instincts, but could also be a non-specific sense of ethics, of right and wrong, the recognition of beauty, a sense of purpose and so on.

Because humans are diverse in our individuality, we also possess certain innate qualities particular to ourselves. When we are unable to act and think according to any or all of these innate desires, because of external restraints, we feel unhappy, unfulfilled, frustrated – people react in different ways.

The society in which we live, the modern world, is designed to suppress these innate desires, to numb us, to tame our life energy and turn us into obedient workers and consumers for the Great Racket. Part of that domination is the concealment of our real status, the denial that there is anything wrong with the way we have been raised and conditioned to live, that we are being denied the chance to live the way we were meant to live, both collectively, in the way we organise our societies, and individually, in being able to follow our personal impulses, release our full potential and play the role we were intended to play in the amazing cosmic explosion of vitality of which we are part.

So people don’t know what is wrong. They find ways of coping with their depression, or taking out their anger, with anything from workaholism to dangerous sports, from antidepressant-addiction to violence. Sometimes this reaction does take on a political form, when the fog clears for a moment and people, particularly young people, get a glimpse of the reality of the prison-world they have been born into and come to the conclusion that things need to fundamentally change. I am thinking of the pre-WWI anti-industrial movement at Ascona, for instance, or the youth revolt of the 1960s. For my generation, this rebellion took the form of the punk scene, and a certain associated cultural mood, which was very much a rejection of consumer society and commercialism as well as of authority.

These movements, or moments, are generally recuperated by the system, of course, with the result that the brief clarity is lost and people go back to being dissatisfied without knowing exactly why. They can even find themselves pouring their frustrated energy into fighting other people with whom they in fact share the same root problem. Such is the complexity of the hall of mirrors built around us that it is extremely difficult to identify the core problems confronting us and very easy to be sidetracked into attacking the wrong targets.

In the light of these difficulties, the best way of orientating ourselves in this insane world is to look within, to connect with, and act according to, the innate values with which we were born.

When we do this on a personal level – by becoming aware of our own gut reactions, our real likes and dislikes, our deeply-held opinions rather than those we adopt in order to be accepted by society, listening to our dreams, to signs and suggestions from the voice within – this amounts to a psychological approach.

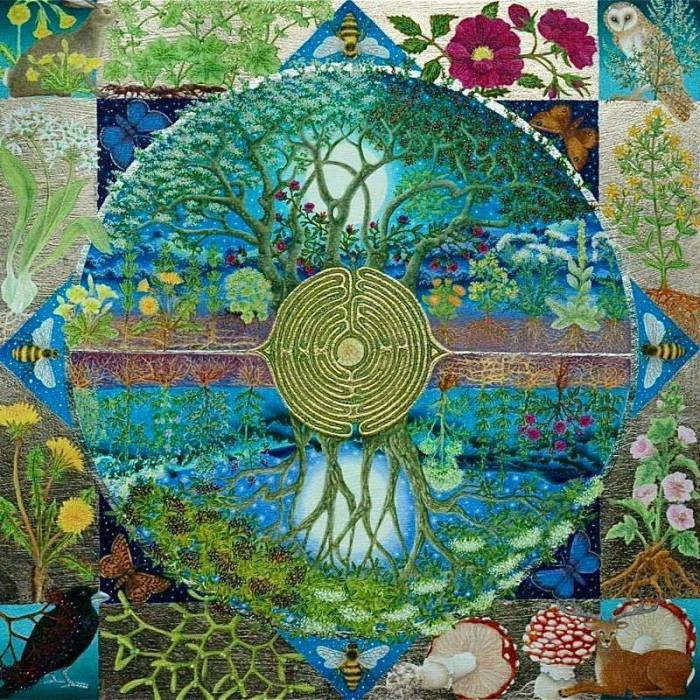

But there is also a cultural means of accessing collective innate wisdom, through exploring myth, folklore, religion, traditional philosophy, art, music and so on.

The two approaches combine in that it is our innate personal intuition that can tell us which cultural sources to follow, such as through our sense of whether or not a certain teaching “feels right”, and it is these cultural sources that can guide us in our personal quest for self-knowledge.

When we have re-sourced our being and thinking in this way, from deep below and high above rather than horizontally from the shallow pseudo-thought of the modern world, we will have the vision and strength to join together with other seekers of the truth and to struggle together to throw off the chains that have held us all down for so long.

On a personal level this is the individuation of which Jung wrote, but on a large scale it would represent humankind rediscovering itself, becoming itself again, getting back on its feet after the blow it has been dealt by the life-stifling criminal system.

CROW: Speaking of Carl Jung, he is also a figure who has been tarred with the brush of Volkisch ideology. I remember, years ago, coming across a book called The Aryan Christ, which attempted to portray Jung as a representative of a retrogressive, reactionary political tendency.

When I think about it now, I’m astounded. How could any intellectually honest person see Jung as a reactionary? To me, he is one of the most inspiring exemplars of a modern sage. You are clearly very inspired by Jung. Could you speak about the importance of Jung’s thought on your work, as well as his connection to Volkisch ideology?

PAUL: I see Jung’s ideas as being a continuation of anarchist philosophy beyond the borders of what is today conventionally defined as “political” terrain. The most obvious connection, I suppose, is with the idea of an innate sense of connection, an inborn capacity for mutual aid. Kropotkin’s concept of an ethics sourced from nature – both an observed exterior nature and a felt inner nature – is close to the idea of archetypes as laid out by Jung.

The source of the anarchist natural ethics is the collective soul described by Jung. There are patterns, structures, that underlie everything in the cosmos, including human thought and consciousness, which cannot be regarded as separate from that overall whole. As I was saying, these patterns manifest themselves on the collective level in the form of myth and religion and in invididuals in the form of unconscious impulses and dreams or of creativity, such as art or music. They are in fact our inner reality, beneath the surface of an individual “personality” adapted to, and often determined by, the dominant society.

This realisation places Jungian thought at loggerheads with the modern assumption that we are born as blank slates on to which society can write whatever it wants without resistance or refusal – that we are “programmable” by other human beings. He is therefore likely to be regarded as “reactionary” by anyone whose “progressive” dream is to reshape the human mind so as to make it compatible with Technik and control.

The system uses this term to insult anyone who questions or opposes the disastrous direction in which it is taking humankind and we are generally conditioned to regard it in negative terms. But if someone with a gun was forcing me and my friends towards the edge of a cliff and certain death on the jagged rocks below, would it be “reactionary” to rush at them and try to overpower them, or rather “revolutionary”? There comes a point where the two words, apparently opposites, mean the same thing!

Yes, the Jungian movement was very much part of the broad volkisch trend, including the scene at Ascona, which is no doubt another reason why it has often been vilified by pro-system propagandists, of which there are very many. Any belief-system based on central control involving the necessary elimination of the sense of tradition, cohesion and solidarity which stands in the way of that control, will inevitably be hostile to ideas of organic autonomy.

It is worth noting that later in his life Jung expanded his horizons well beyond Europe to embrace the vision of a World Soul possessed by humanity as a whole. Although this might seem, superficially, to be a better fit for the globalist ruling system, his emphasis on innate access to primal truth remained a threat to the dominant materialist dogma. Jung was a latter-day mouthpiece for the most ancient of ancient wisdoms and points us to a domain, way above the flat sterility of “progressive” materialism, where we can regroup and shake off the modern sickness.

CROW: In our correspondence, you have referred to the influence of the anarchist psychologist Otto Gross on Carl Jung. Would it be an exaggeration to say that Gross converted Jung to anarchism? Should Jung be considered an anarcho-perennialist?

PAUL: Gross was certainly a big influence on Jung, who had previously been rather trapped in a rigid middle-class outlook in his private life. I suspect that he inspired Jung to develop his work in a direction which allows the likes of you and to me to recognise it as being an extension of our anarchist philosophy, even though Jung, to my knowledge, never described himself as an anarchist.

In his own writing, Gross clearly provides the link between Jungian thought and anarchism, not least on the question of individuation. Gross wrote, for instance: “The earlier and more intensely that the capacity to resist authority and external intervention begins to take up its protective function, the more the wrench of conflict is aggravated and rapidly deepens and intensifies”.

When Jung went on to express the same viewpoint throughout the rest of his life, albeit in the context of psychiatry, he was still expressing the anarchist view of individual self-realisation of which Gross had written.

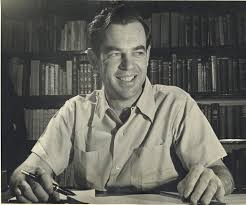

CROW: In addition to Jung, you are clearly a big fan of Joseph Campbell. I think that his idea of “Following your Bliss” offers a possible corrective to the sometimes joyless leftist framing of political struggle as a process wherein the desires of the individual are subordinated to some kind of moral imperative represented by some sort of reified idea of “The Movement”, “The People”, etc. In recent years, political activism in rich countries has often been motivated by guilt, moral duty, and self-sacrifice. Personally, I suspect that we might have more success if we were to emphasize the anarchist project as a joyful pursuit of the deepest aspirations of one’s soul.

Personally, I believe that this message is at the core of the work of both Jung and Campbell, as well as Alan Watts and others. Could you please speak a bit about the influence that Joseph Campbell has had on you, and what you think his message has to offer us today?

PAUL: Campbell is one of several writers with whom I became familiar thanks to my former partner, Julie, who was (and still is, no doubt!) a self-taught expert on everything to do with mythology. While I was already interested in folkore and myth, and felt that it was something important for a healthy society, it was only through reading Campbell, as well as Mircea Eliade, Robert Graves and Jung, that I gradually realised that recognition of its importance formed part of the overall philosophy towards which I was striving.

Particularly important with Campbell, perhaps, is his emphasis on the underlying unity of human thought. This universalist outlook seems to be unpopular these days and is sometimes confused with a top-down imperialistic attitude which denies diversity. But if one starts from the knowledge that the whole universe is one, which is common to all traditional teachings, it necessarily follows that the whole of humankind also amounts to one living entity, within that. Identifying this human universality is not to deny diversity but to understand that humankind as a whole is the enabling entity which contains diversity and allows it to flourish, in the same way as that identifying the branch of a tree does not entail denying the existence and beauty of its twigs and blossom!

Campbell also emphasised the underlying innate pattern in everything, including our individual and collective minds – the natural order that gives meaning to anarchism and its conviction that artifically-imposed “order” is both unnecessary and harmful.

CROW: How about Alan Watts? Would you care to speak about the importance of his work, and why you think it continues to be relevant today?

PAUL: I came across Watts slightly later than the other authors we’ve discussed. In fact, I was explaining the content of my first book, The Anarchist Revelation, to a woman at a friend’s party back in England and she thought it sounded very much in line with Watts’ thinking. She was right, of course, as I discovered. Again, he puts great emphasis on oneness and natural order, making the connection with Taoism.

Watts is very accessible and he was able to communicate the essence of traditional thinking to people who perhaps would never get round to reading René Guénon. There is a New Age surface to his work which appeals to a wide readership and yet I feel he remains true to authentic wisdom and does not drift off into woolly pseudo-spirituality.

I very much appreciate the depth of his holistic thinking, which leads him to reject the idea of cause and effect in favour of the notion that both these apparently separate events are simply aspects of one single process. There is the basis in his work, and that of the other thinkers featured on the Organic Radicals site, for the broad-ranging and powerful new-old philosophy that we so badly need to carry us out of the toxic and authoritarian modern nightmare and into a free, natural and happy future.

The updated booklet can be found here.