From: FASCISM REBRANDED: EXPOSING THE GREAT RESET

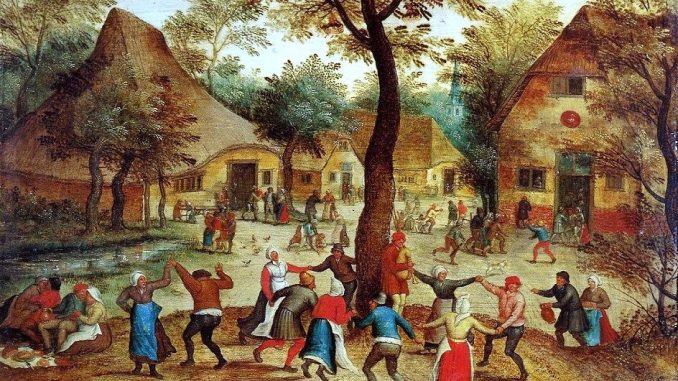

Nostalgists conjure up a vision of the past in which people lived peacefully and happily in small communities, close to nature, free from outside interference, producing just enough for their collective needs and organising themselves in a spirit of mutual aid and social solidarity.

Idealists, on the other hand, dream of a future in which people live peacefully and happily in small communities, close to nature, free from outside interference, producing just enough for their collective needs and organising themselves in a spirit of mutual aid and social solidarity.

It is a familiar theme of anarchist (and some other left-wing) thinking that these idealistic visions, of the past and the future, are in fact one and the same vision.

But which is the original? When we romanticise the past, are we projecting our hopes for the future on to it?

Or is it a question of basing our dreams of the future on a mythologised romantic past?

I would argue that neither is the case. What we are “projecting” in each instance is an archetype of how we think society could be organised.

It is an “ideal form” (to use an immensely unfashionable neoplatonic term), a kind of abstract template.

Of course, real life will never correspond exactly to the ideal, which is why attempts to prove that this model has existed in the past will always be problematic.

This is also why people are often sceptical about the potential for it becoming real in the future – we all know that real life is never perfect.

But this ideal society does exist – on an abstract level within the collective mind of the human species.

It is a possibility, as a way in which people could live, if they wanted.

More than that, it is the model of the way we should live.

This ideal notion of how society should be arranged is innate. It is as much a part of the human psyche as the idea of living in a herd is part of the cattle psyche, or building dams is part of the beaver psyche.

Because we, as modern humans, have been brought up to think that all knowledge has to be learned, we can forget that this is not the case within nature as a whole.

Even when they have not had the chance to learn from their parents’ behaviour, other creatures know, instinctively, how to go about their lives.

Cuckoos, for instance, are born, in the nest of another species, knowing where to find their own cuckoo African wintering grounds, thanks to what scientists call an “innate migration programme“.

Humans are certainly less controlled by instinctive behaviour. We, like baboons and other apes (as Eugène Marais described) have been able to separate ourselves from instinct to some extent and are thus freer to adapt to external circumstances.

But those instincts are still inside us somewhere, even if they do not necessarily control our behaviour.

Notions of what exactly is “right” or “wrong” can, for instance, vary between cultures, but the overall idea of justice – that there is such a thing as “right” and “wrong” – is shared by all of them.

Peter Kropotkin wrote in Ethics that “the sense of Mutual Aid, Justice, and Morality are rooted in man’s mind with all the force of an inborn instinct”.

Even if certain individuals and groups have overridden this impulse in favour of narrow self-interest, the collective desire for solidarity, freedom, autonomy and a natural way of life remains innate to the human species as a whole.

This is why this ideal – which today we might call anarchy or real socialism – keeps welling up time and time again throughout history.

This is also why the self-interested ruling elite have to devote so much time and resources into discrediting and suppressing this ideal.

If it became a physical reality, they would lose all their power, status and wealth.

So they do all they can to prevent it from ever rising to the surface of the collective mind and inspiring people into powerful and unstoppable revolt against the unnatural infrastructures which obstruct its realisation.