by Winter Oak

- Charles the Great Resetter

- Global goals

- Impact imperialism

- Powerful players

- Banksters, cheats and spooks

- The bringer of light?

- Neo-colonial land-grabbing

- Shaping history

When the Great Reset was officially launched in 2O2O, it was not done so by Klaus Schwab or Bill Gates, but by Charles, Prince of Wales, heir apparent to the British throne.

Born in Buckingham Place in 1948, Charles is best known worldwide for his failed marriage to Lady Diana Spencer, who died in a road crash in Paris in 1997, a year after their divorce.

His official website announced on June 3 2020: “Today, through HRH’s Sustainable Markets Initiative and the World Economic Forum, The Prince of Wales launched a new global initiative, The Great Reset”.

A royal tweet declared: “#TheGreatReset initiative is designed to ensure businesses and communities ‘build back better’ by putting sustainable business practices at the heart of their operations as they begin to recover from the coronavirus pandemic”.

This may come as a bit of a surprise to those who see Charles as a bumbling but affable figure, who talks to his plants, loves traditional architecture, protects nature and tries to help young people get along in life.

But the reality, as we will show here, is that he is the head (or the very willing figurehead) of a vast empire of nefarious financial interests hiding hypocritically behind a facade of charitable philanthropy.

Charles has been very busy over the last 50 years or so, establishing an alliance of organisations called The Prince’s Charities, which describes itself as “the largest multi-cause charitable enterprise in the United Kingdom”.

These have also spread overseas to create a bewildering global web of trusts, foundations and funds.

To make things simpler, we will focus here on just a few of the better-known organisations, starting in the the UK with Business in the Community.

This body describes itself as “the largest and longest established business-led membership organisation dedicated to responsible business”, having been initially established in 1982 as The Prince’s Responsible Business Network.

Its agenda is very much in line with all the key elements of the Great Reset.

It declares, for instance: “Business in the Community (BITC) is working with business to accelerate the pace and scale of action to deliver against the United Nations Global Goals, also known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)”.

The great news for Charles’s money-loving entourage is that “running their businesses responsibly” in line with the UNSDGs “also opens business market opportunities”.

Business in the Community boasts its own WEF-style “Future Leaders Board” and in 2017 was already insisting, like Klaus Schwab, that “business must ensure an inclusive digital revolution”.

Its report called “A Brave New World?” features all the familiar Great Reset “priorities”, such as inclusivity (“Build digital access, capability and confidence to allow all to benefit from the digital economy”) and lifelong learning (“Prepare employees. Provide digital skills and lifelong learning to create an adaptable workforce”).

It looks ahead to a Fourth Industrial Revolution (“Anticipate automation. Create new roles, where technology complements humans, and support communities to manage the transition”) with bigger profit margins naturally being its aim (“Transition to new business models that cut waste and increase asset productivity”).

There is an early mention of the “track and trace” phrase which became so familiar during the lockdowns (“Track, trace and resolve”) with a plug for Blockverify, “a London-based start-up that uses technology to track, record, and verify products in a way that is permanently logged in the blockchain… Blockverify has been piloting solutions with pharmaceutical and beauty companies”.

The report promotes smart agriculture in the form of Unilever’s Marcatus Mobile Education Platform, “a collaboration between Unilever, Oxfam and Ford Foundation to train smallholder farmers in rural areas” which aims for “additional farm revenues of £1.5 trillion by 2030”.

It concludes by giving “thanks to our corporate partners, Barclays and Fujitsu, for supporting our programme of work to create an inclusive digital revolution”.

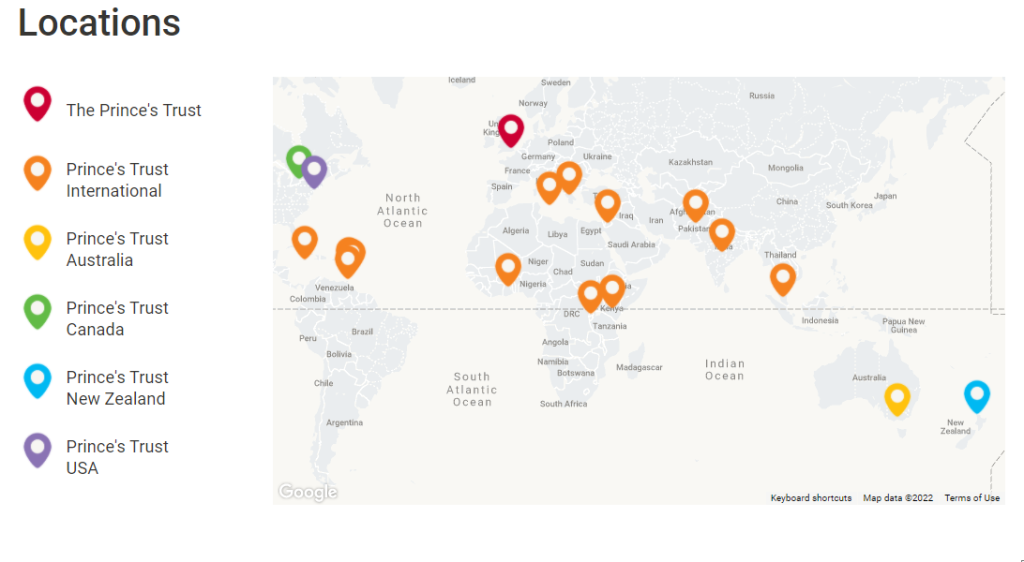

The Prince’s Trust Group expands this same agenda across the Commonwealth, the vast sphere of influence formerly known as the British Empire.

It describes itself as “a global network of charities” delivering “education, employment, enterprise and environmental projects that enable young people and communities to thrive”.

It is all about “transforming lives and building sustainable communities”, it seems.

One of its reports tells us: “During 2020/21, together with our partners we supported 60,146 young people in 16 countries across the Commonwealth and beyond: Australia, Barbados, Canada, Ghana, Greece, India, Jamaica, Jordan, Kenya, Malaysia, Malta, New Zealand, Pakistan, Rwanda, Trinidad & Tobago and the United Kingdom. We also began our work in St Lucia and the USA”.

The Prince’s Trust is joined in this task by another important node of Charles’ network, the British Asian Trust, as we will shortly see.

The impact industry is a sinister entity which, over the last few years of research, we have found lurking under every dubious stone we have turned.

For more info, check out our articles on Extinction Rebellion, Ronald Cohen, intersectionality, the WEF Global Shapers, Guerrilla Foundation, Edge Fund and also our general overview.

Impact profiteering is very much tied in with the Great Reset and its Fourth Industrial Revolution, which aims to set up the infrastructure through which this new form of digital serfdom can be imposed.

Inevitably, then, the impact agenda is very present throughout Charles’ empire, even if somewhat hidden from casual view.

Sometimes it is just the word itself that gives the game away.

Business in the Community, for instance, says on its site that it works with its members “to continually improve their responsible business practice, leveraging the collective impact for the benefit of communities”.

“Impact” crops up three times on the introductory page.

It appears again on the page consecreated to BITC’s entirely predictable commitment to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, those cornerstones of impact capitalism. The term “positive impact” is here linked to another related buzzword, “purpose”.

The impact theme is also very much embraced by The Prince’s Trust, which is very keen on “digital and blended programmes” and “online business simulation games”.

In line with the Great Reset promoted by its founder, it used Covid to advance a hyper-industrial agenda, describing in one post how it had been measuring its “digital impact”.

It was pleaed to report that 61% of its respondents said “online learning had supported them to make changes in their life, with the majority developing new skills and making plans for the future”.

One of the tools which the Trust uses for what it worryingly terms “digital programming” is something called Vibe Check.

This bespoke programme, aimed at young people, is a “free (fancy that!) interactive personal development tool delivered via WhatsApp, that creates a safe and supportive online space for them to develop key life skills”.

“The programme has piloted in Barbados and Ghana during 2020 and early 2021, using innovative automation technology to tailor each young person’s experience with the service.

“Designed for the needs of young people in each country it rolls out in, Vibe Check focuses on confidence, communication and managing feelings in Barbados, and self-employment and entrepreneurship in Ghana”.

This obsession with developing “new digital processes for gathering data”, hidden behind a do-good facade, is classic impact-think.

Indeed, the Prince’s Trust International boasts its very own Head of Impact, Diletta Morinello, a professional “impact measurer”.

In January 2020, just before the Covid moment, Morinello was recruiting a data analyst “as we start our exciting new 5-year strategy” and “significantly upscale our operations”.

The role was “to ensure our data is robust and supports our ability to accurately and effectively monitor our impact on young peoples’ [sic] experiences of education and employment as well as our financial performance and fundraising.

“Impact will need to be measured across a range of programmes or interventions, with a range of stakeholders across the world”.

Impact, data, stakeholders… three terms from the same familiar crib sheet.

It is, however, with his British Asian Trust that Charles exposes most fully his involvement with the insidious world of impact imperialism.

He founded this organisation in 2007 with a group of well-connected British Asian businesspeople.

Although the British Asian Trust prefers the term “social finance”, it does little else to hide its impact agenda.

Its website even proudly displays a recommendation from the “father” of impact investment Ronald Cohen, who declares: “What the British Asian Trust is doing in social finance is truly groundbreaking: it is capable of delivering vital social improvement at scale”.

Indeed, as we have previously reported, Cohen gives an approving mention to Charles and the British Asian Trust in his 2020 book Impact: Reshaping Capitalism to Drive Real Change.

The Trust, of course, claims to be “improving” the lives of children and young people in Asia “in line with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4 on quality education”.

It says: “The Quality Education India Development Impact Bond (QEI DIB) is an innovative results-based funding mechanism that aims to improve learning outcomes for more than 200,000 primary school children”.

And then it adds: “As the QEI DIB progresses, we aim to create an education rate card, setting out the costs of delivering specific outcomes at scale. Such a card can be used by government and funders to make informed policy and spending decisions and improve education across the whole country”.

This is what impact is all about. The “cost” of meeting UNSDGs is calculated and “stakeholders” take on this cost from public purse. If the “outcomes” tick all the right boxes they will be reimbursed, plus a little extra to make their “investment” worthwhile.

In the meantime, the lives of these children, bundled together “at scale”, are turned into financial commodities – like the bundles of sub-prime mortgage debts that prompted the 2008 crash – which can be tracked, traced and traded in real time via 5G/6G and the “inclusive” global digital panopticon.

Speculators can bet on the “success” of these children’s lives or against it – little matter, as long as they are available as products for this vast new profitable market.

As we have previously warned, “social finance” or impact investing reduces human beings to the status of potential investments, sources of profit for wealthy ruling vampires.

It is a digital slave trade.

So what kind of people and organisations are involved in Charles’ global network?

Let’s start with Business in the Community. This label is probably intended to conjure up fond images of tiny cornershops in English market towns (like Grantham?) or of organic Buddhist basket-weaving start-ups in Charles’ pseudo-traditional Poundbury development.

But no. As we would expect from the launcher of the Great Reset, the project is a typical corporatist mixture of public and private sector, uniting loyal servants of the British empire with their extremely well-heeled friends in the world of big business and high finance.

BITC’s dauntingly long list of members includes the likes of Accenture and Unilever (both hailed by Cohen for their participation in his nefarious impact scam) and Big Pharma businesses AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer.

While the BBC, Sky, Facebook and Google presumably constitute the propaganda and censorship wing, British Airways, easyJet, Heathrow Airport Limited, Shell UK and BP were no doubt all included for their special contribution to environmental sustainability.

Charles’ passion for the health of his family’s grateful subjects is reflected in the inclusion, alongside Knorr’s Quick Soups manufacturers Unilever, of Greggs and PepsiCo UK.

We also find the likes of the Bank of America, McKinsey (the US consultancy firm controversially employed by Emmanuel Macron in France) and Morgan Stanley (the WEF partner and impact investor remembered for its financing of both Hitler and Mussolini).

Other Business in the Community members are arms dealers Rolls Royce and Thales Group, superb examples of what Charles has in mind with “responsible” business activity.

The organisation is governed by a Board of Trustee Directors. This is chaired by Gavin Patterson, president and chief revenue officer of Salesforce, the cloud computing business headed by billionaire Marc Benioff, owner of Time magazine and inaugural chair of the WEF’s Center for the Fourth Industrial Revolution in San Francisco.

Another director is Dame Vivian Hunt, senior partner, UK and Ireland, of the aforementioned McKinsey. A member of the secretive Trilateral Commission, she is the former chair of British American Business, an exclusive transatlantic business networking group.

One of the vice-presidents is Sir Mark Weinberg, “a South African-born British financier who co-founded J. Rothschild Assurance, which later became St James’s Place Wealth Management, and is chairman of blockchain company Atlas City Global“.

The advisory board features Sir Ian Michael Cheshire, formerly chairman of Barclays UK and currently chairman of Menhaden plc with its “long only, multi-asset investment strategy which seeks to provide the best balance between risk & reward across equity, credit & private universes” offering “asymmetric risk-reward pay-offs”.

Alongside this banker sits none other than Frances O’Grady, general secretary of the UK’s Trades Union Congress (TUC). As befits a representative of the British working class, O’Grady is also a non-executive director at the Bank of England.

Finally, on the BITC’s Community Leadership Board we find none other than Owen Marks of everybody’s favourite vaccine manufacturer, Pfizer.

There he incarnates the striking overlap between the world of Big Pharma and the world of “woke” impact-intersectionality, co-chairing the Pfizer UK Inclusive Diversity Group with its focus on “OPEN (LGBTQ), Ethnicity, Gender, DisAbility and Cross Generational and Social Mobility”.

Let’s next turn to The Prince’s Trust Group, the global network of charities founded by Charles in 1976.

The UK entity involves very much same kind of people as Business in the Community.

Its council is chaired by John Booth, an “entrepreneur and philanthropist” who boasts “a range of venture capital interests in e-commerce, media and telecommunications”.

It features two former partners at Goldman Sachs: Michelle Pinggera and Ian Mukherjee, who went on to found Amiya Capital, a “global emerging markets fund”.

There is also Suzy Neubert, former global head of distribution at JO Hambro Capital Management, and Mark Dearnley, previously a “digital transformation” advisor with global management consulting firm, Bain & Company.

The council’s vice-president is Michael Marks, former chairman of Merrill Lynch Investment Managers and founding partner of MZ Capital and NewSmith Capital Partners LLP.

It is informative to note the people and businesses with which the Prince’s Trust group is enmeshed worldwide.

In New Zealand, chairman of the Prince’s Trust board is Andrew Williams, co-chairman of Alvarium – “With $15 billion in assets under management globally, Alvarium is a collaboration between wealthy families, entrepreneurs and institutions in Asia, the Gulf and Americas”.

The Australian entity’s corporate sponsors include Macquarie, Australia’s largest investment bank, while in Canada, the Prince’s Trust is supported by Finistra (working hard “to accelerate digital banking”) and by Bank of America.

Its supporters also include Scotiabank, KPMG and arms dealer Lockheed Martin.

Over at the British Asian Trust, one member of the Board of Trustees is Farzana Baduel, former vice-chair of business relations for the Conservative Party and founder/CEO of Curzon PR.

She appeared in The Times in May 2021 to explain how much she loved “remote working”, that mainstay of the “New Normal” promoted under the Great Reset.

Another is Varun Chandra, managing partner of “London-based corporate intelligence specialist” Hakluyt, whose astonishing recent £12.8 million rise in profits was “helped by the reduction in staff travel thanks to the pandemic”, according to The Times.

In the words of one media report, “Hakluyt is an ultra secretive firm whose client list reads like a who’s who of the business world with corporations retaining their services for strategic intelligence and advice as they look to expand operations”.

The British Asian Trust site says of Chandra: “Trained at Lehman Brothers, he went on to help build a regulated advisory firm for former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair“.

Also on the board are Dr Shenila Rawal (who previously worked for the World Bank) and Ganesh Ramani, former partner at Goldman Sachs.

Ramani in fact has a family connection to the Trust’s Big Chief, having married Ruth Powys, widow of Mark Shand, brother of Charles’s wife Camilla.

Vice-chairs are Asif Rangoonwala (once described by The Independent as “powerboat playboy, bakery baron, property plutocrat”) and Shalni Arora, who has a background in Big Pharma with AstraZeneca and DxS Ltd and is the wife of retail magnate Simon Arora of B&M Bargains.

Chair of the Board of Trustees is investment banker Lord Jitesh Gadhia, who has worked for Barclays Capital, ABN AMRO and Baring Brothers.

He was previously senior managing director at global investment business Blackstone in London. On being appointed there in 2010, he enthused: “Blackstone’s powerful network of relationships, access to capital and expanding geographic reach, across developed and emerging markets, offers a unique proposition for clients”.

Gadhia was also – surprise, surprise! – a World Economic Forum Young Global Leader.

5. Banksters, cheats and spooks

From any genuinely ethical vantage point, the business activities of those involved with Charles’ empire are, in themselves, cause for concern.

But the problem goes further than that. The amount of controversy and scandal surrounding numerous participants in his various projects makes one wonder how someone who likes to be referred to as “His Royal Highness” can associate with so many examples of what most of us would regard as low life.

Here are some illustrations:

HSBC is the Prince’s Trust’s Global Founding Corporate Partner and is praised in its Impact Report for its “transformational investment in young people”, being identified as “one of our most committed and loyal supporters”. Never mind that the British-based bankers have a long history of vast tax avoidance schemes and criminal activity such as money laundering. Dubbed “gangster bankers” involved in “stupefying abuses”, Charles’ loyal supporters even “hooked up with drug traffickers and terrorists”, explains this 2013 article.

KPMG (Business in the Community and Prince’s Trust, Canada) has faced “multiple accusations of negligence, fraud, and conflicts of interest stretching back years” and was recently involved in a giant “cheating scandal“.

NatWest (Business in the Community) was fined £264.8 million in December 2021 for failing to comply with money-laundering regulations.

Bank of America (Prince’s Trust) faced boycott calls after spying on its customers’ activities for the FBI with regard to the January 6 2021 protests in Washington, DC.

PwC (Business in the Community) has a “long history of controversies” all over the world, not least in India, where it is said to have “a chequered past” with the tax authorities.

Goldman Sachs International (Business in the Community, Ganesh Ramani of British Asian Trust) is afflicted by so many “controversies” that even Wikipedia devotes a whole page to them!

Lockheed Martin (Prince’s Trust, Canada). The arms dealer is notorious for its many bribery scandals.

Macquarie. (Prince’s Trust, Australia). Australia’s largest investment bank was involved in a recent $80 billion controversy labelled the “biggest bank scandal in history“.

Scotiabank (Prince’s Trust, Canada) had to pay out more than US$120 million dollars in 2020 because of its price-manipulation activities.

Jitesh Gadhia (British Asian Trust), a Conservative Party donor in the UK, was involved in David Cameron’s “cash for access” scandal in 2014 and in 2018 he was accused of a conflict of interest because he had become a director of fracking business Third Energy, while also being a non-executive director at UK Government Investments.

Shalni Arora (British Asian Trust). Her husband Simon hit the headlines in 2021 for handing himself a massive payout of £30 million. His firm, B&M bargains, had enjoyed a surge in sales because of its “essential” status during Covid lockdowns.

Varun Chandra (British Asian Trust). His firm, Hakluyt, says The Times, advises FTSE 100 companies and “was founded 27 years ago by former MI6 intelligence officers”. An article in The Evening Standard describes the business as “very secretive Mayfair company full of spooks” and “a convenient rest home for MI6 men”. “The company attracted unwelcome publicity in 2001 when it emerged it had used an undercover agent known as Manfred to penetrate environmental groups targeting Shell and BP”. And Hakluyt was again forced into the media limelight in 2012 due to “the mysterious death of one of its occasional investigators in a Chinese hotel room”.

Finally, Charles himself has been caught up in various controversies over the years, not least regarding his role in helping arms dealer BAE Systems sell fighter jets to Saudi Arabia.

Reported Scotland’s The National: “MP Margaret Ferrier said Princess Diana would have campaigned against its bombing raids on Yemen, which allegedly involve the use of banned cluster munitions, and claimed Charles was part of a ‘great effort’ to maintain the market”.

And then, of course there there was that unfortunate incident in the Paris tunnel back in 1997…

6. The bringer of light?

One particularly intriguing figure in Charles’ global network is another man who likes to be known as “His Highness”, namely The Aga Khan.

Khan is none other than the Global Founding Patron of the Prince’s Trust and, its site tells us, “supports the delivery of The Trust’s work in the UK and Canada and through local partners in India, Jordan, Kenya, Pakistan, Rwanda and the Caribbean (Barbados, Trinidad & Tobago and Jamaica)”.

The business magnate has British, Swiss, French and Portuguese citizenship and his fingers in many a global pie.

One 2016 profile explains: “As founder and Chairman of the Geneva-based Aga Khan Development Network, he spearheads an organisation that employs 80,000 people in 30 countries, and spans non-profit work in poverty-stricken and war-torn areas of the globe, along with a huge portfolio of very-much-for-profit businesses in sectors ranging from aviation and energy to telecommunications, pharmaceuticals and luxury hotels”.

Khan’s net worth has been estimated at $13.3 billion and he is described as one of the world’s fifteen richest “royals”, although he does not actually rule over any particular geographic territory.

Instead he is the spiritual leader of some 20 million Ismaili Muslims, who donate significant sums to him and worship him as the “bringer of light”.

Khan is a personal friend of Charles and his mum, Queen Elizabeth II, as well as of the Spanish king Juan Carlos.

He is also said to have long connections to British intelligence services and other deep state networks.

Khan has been involved in a number of international scandals.

In 2012 it emerged that, although resident in France, he had been “exonerated” from paying any tax by the country’s former president Nicolas Sarkozy.

This, explained The Daily Mail, meant that he could protect his vast fortune across the Channel “despite being worth as much as £6 billion and owning mansions, yachts, private jets, some 800 race horses and even a private island in the Bahamas”.

Then, in 2017, controversy broke out in Canada when it was discovered that prime minister Justin Trudeau had spent a holiday on a private Caribbean island owned by Khan.

While he was there, he also took a ride in the bringer of light’s private helicopter.

Since the Khan’s foundation “receives millions from the Canadian government”, questions were asked about a certain conflict of interest!

Trudeau reassured the public that there was nothing to worry about because “the Aga Khan has been a longtime family friend”.

But he nevertheless became the first Canadian prime minister to be found in violation of ethics law and was forced to publicly apologize.

Khan is also close friends with the Rockefellers and the Rothschilds.

In a speech at New York’s Plaza Hotel in October 1996, David Rockefeller said: “His Highness The Aga Khan is a man of vision, intellect, and passion. I’ve had the pleasure of knowing him for almost forty years, ever since he was an undergraduate at Harvard and a roommate of my nephew Jay Rockefeller”.

For his part, Khan expressed “warm thanks” to Rockefeller, adding: “He, his family, and his philanthropic organisations have been close to my family, our work, and me, for many years. I admire them for their consistent and exemplary commitment to world issues”.

A message from their mutual pal Lord Rothschild praised Khan for his “promotion of private sector enterprise and rural development”.

7. Neo-colonial land-grabbing

Khan, Rockefeller and Rothschild are also united by their common membership of the 1001 Club of the WWF.

According to researchers, this little-known group was set up in the 1970s by individuals including Charles’s dad, the late Prince Philip, and Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands.

As we noted in this report, Bernard used to be in the Nazi SS, before founding the WWF.

He also chaired the Steering Committee of the Bilderberg Group, of which WEF boss Klaus Schwab was a fellow member.

Bernhard was also honorary sponsor of Schwab’s third European Management Symposium at Davos in 1973, when the body which was to become the World Economic Forum first adopted a more overtly political stance, by agreeing a document which became known as “the Davos manifesto”.

The WWF is notorious for throwing indigenous people off their land on behalf of its big business friends under the false green flag of “conservation” and is today very prominent in the industrial-financial lobby calling for a New Deal for Nature.

For a full analysis of all this, we recommend the excellent work of the No Deal for Nature campaign, Survival International and Talking Africa.

Here, we will simply note that Charles is very much on board this agenda, endorsing the idea of “natural capital” and indeed launching a new “natural capital alliance”.

But then that is to be expected, because he is president of WWF-UK and “proud” to be so.

He declares on the WWF site: “I have long admired its efforts to tackle the many threats to the world’s wildlife, rivers, forests and seas. And I have come to see how effectively it uses its expertise and international reach to challenge the causes of degradation, such as climate change and the unsustainable use of natural resources”.

Yet again, the worthy-sounding language masks a very different reality: in this instance a newly accelerated wave of the global land-grabbing which has been a feature of the profit-driven British empire for centuries.

8. Shaping history

If Charles ever emerges from his 70-year stint in the Windsors’ waiting room, he will become King Charles III and thus historically linked with his two predecessors of the same name.

Charles I, who became king in 1625, was the last of the ancien régime, a defender of the feudal order. Having been found guilty of tyranny and treason, he was beheaded in front of the London crowds in 1649 (see above).

This was the apex of an English Revolution which, like so many others, was quickly shunted in a direction contrary to the interests of the mass of people who had fought and died for it.

When Oliver Cromwell crushed the radical elements in his New Model Army, at Burford, he was thanked with a celebratory banquet by the financiers of the City of London.

From that moment onwards, the focus of the country was on commerce, expansion and exploitation, including, of course, the slave trade.

Starting with Cromwell’s bloody re-occupation of Ireland, the 11-year period of republican rule, known as the Commonwealth, saw Britain’s empire begin to take shape, with the grabbing of Jamaica, Surinam, St Helena, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

When the executed king’s son, Charles II, took the throne with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 it was as a “constitutional” king, beholden to parliament and happy to act as a figurehead for the military-mercantile entity known as the British Empire.

The future Charles III seems to be on course to combine the worst elements of both predecessors, fusing old-style feudalism with modern corporate control to forge a “sustainable” global empire built on digital serfdom and impact vampirism.

But it is important to remember that conspiracies cannot succeed if people are wise to what is happening.

By researching and exposing wrong-doing, we can shake off our status as helpless and passive spectators of history in order to become active and engaged participants, part of the resistance.

Charles and his ruling-class collaborators have to dress up their insidious agenda as “doing good”, as “philanthropy” or “conservation”, because they know that otherwise the rest of us would not go along with it.

Once this illusion has been destroyed and the horrible reality exposed, then decent people everywhere will turn their backs definitively on these vile parasites and their evil empire of exploitation.

See also: