by Fernando Andacht

Preface

by Margaret Anna Alice

I am honored to publish this guest piece by Fernando Andacht, semiotician, eXtramuros Magazine essayist, and professor in the Theory Department of the Facultad de Información & Comunicación at Universidad de la República in Montevideo, Uruguay.

Over the past couple of months, I have developed a profound connection with my cherished compadres at eXtramuros, which has published Spanish translations of Letter to a Covidian (Carta a un Covidiano: Un Experimento de Viaje en el Tiempo) and Letter to a Scientifically-Minded Friend (Carta a un Amigo con Mentalidad Científica). Translation of my subsequent letters is already completed or underway for future issues of eXtramuros.

This relationship began with my discovery of Fernando’s exquisite essay Un Nuevo Diario del Año de la Plaga Tres Siglos Después: La Peste, la Tanda, y la Identidad Perdida through an eloquent Facebook post by Andrea Grillo, who describes Fernando as taking “a walk with Margaret Anna Alice in an imaginary encounter” and closing his essay with “‘a hope that endures’ … leaving the door open to the capacity of wonder.”

I was so intrigued by Andrea’s description, I immediately sought out Fernando’s article. Even in its clumsy Google translation, it exuded a rare combination of piercing intelligence, sardonic wit, warmth of spirit, and poetic beauty.

I expressed my appreciation at his post about the essay and asked Fernando if he would be willing to translate it into English, to which responded:

“Margaret Anna Alice what a wonderful surprise to be read by one of the sources of inspiration for my essay in eXtramuros. And to meet her here, in this not always welcoming medium! The moment I shared your Letter to a Covidian with the other members of the editorial board of our on line publication, eXtramuros, the reaction was immediate & unanimous: it had to be translated right away! And so it was, it is part of our new issue.… But now I’d very much like to translate my essay into English, so that we can continue with this unexpected but delightful dialogue.…”

After I published Letter to a Scientifically-Minded Friend, Fernando wrote:

“Just a great writer, who values the fine irony, literary creativity but doesn’t leave aside the best available data about cheap therapy … unmissable & urgent.”

When I thanked him for his compelling introduction, he wrote:

“The enthusiam of reading your new essay made us feel you are part of the group of the eXtramuros magazine. We loved your text and we felt it had to be read by those who do not read English. It was a very enjoyable work to do our best not to lose the richness of your language and to do justice to the many fine and most timely ideas. There are so few of us on this side of the sad and tragic rift that has taken over the world that when we find somebody who shares our ideas and writes as beautifully as you do, it’s a sort of ethical imperative to make your work known to those for whom English is a formidable linguistic barrier.… [Translating my essay] would be a great way to exchange signs on what most matters right now, namely, resist as much as possible this vast alienating narrative that is spread on so many channels and at every minute of the day.…”

Narendra Casandra was kind enough to translate that letter, which appeared in the October 24, 2021, edition of eXtramuros.

Then, when I published Letter to a Holocaust Denier, Fernando posted:

“She did it again, admirable writer Margaret Anna Alice, produced a magnificent text, where she gathers a tremendous and fair diagnosis of the health situation towards the end of October 2021.… With elegant irony and proud sarcasm, when necessary, Margaret Anna Alice articulates a lucrative thought and brings a remarkable amount of relevant information about what the mass media and powerful networks are silent cowardly and complicit.… Necessary Reading.”

I then had the joy of meeting one of my other translators, Luis Anastasía, when he bought me some coffee. Here is his post for those who would like to read the full exchange. He introduced himself as follows:

“I am from Uruguay. My friend Fernando Andacht sent me your Letters. Amazing, heroic, titanic is your excellent work, very well grounded and better written. I translated some of your Letters for those who cannot read English, for their extraordinary literary value, for their writing style, and for all the light that is shining on this black hole we are falling into.”

When I expressed my gratitude for his work, he responded:

“Wooow… I feel very excited. On very special occasions, when someone I admire very much, says something like you said to me, it is a very special award for me. And yes, my last translation was Letter to a Conspirator. I took the greatest care to maintain the intensity of your text, every word, every sentence, the cadence and rhythm with which it conveys so much information.…”

He offered to share his translations for publication at my blog, so at some point, my Spanish-speaking readers will be able to enjoy select pieces translated into their native language with the utmost passion by my Uruguayan kindreds.

A New Journal of the Plague Year Three Centuries Later

The Pandemic, the Commercial Break, & the Lost Identity

Written and self-translated by Fernando Andacht (read original in Spanish)

Today, I am going to write something that is akin to a pandemic chronicle, without pretending to emulate the great novelist Daniel Defoe—who in addition to narrating the adventures of the castaway Robinson Crusoe, was the author of A Journal of the Plague Year, published almost exactly three centuries ago, in 1722. It is worth transcribing the eighteenth-century style introduction of the work that Defoe wrote in the first person, thus adopting the voice of an actual witness:

“… being Observations or Memorials of the most remarkable occurrences, as well public as private, which happened in London during the last great visitation in 1665. Written by a CITIZEN who continued all the while in London. Never made publick before.”

I have drawn inspiration from it, and I also draw breath through no mask. I need fresh, unclogged air to start writing a triptych of my personal journal of the globalized plague in the fine company of that magnificent English chronicler who recreated life under the siege of the bubonic plague a few years later.

Defoe’s description of one of the sources of the panic that flooded the streets of London in the second half of the eighteenth century serves as a prologue to what I propose below as being the largest source of terror that has been circulating for over a year and a half on all television screens 300 years later:

“The apprehensions of the people were likewise strangely increased by the error of the times; in which, I think, the people, from what principle I cannot imagine, were more addicted to prophecies and astrological conjurations, dreams, and old wives’ tales than ever they were before or since. Whether this unhappy temper was originally raised by the follies of some people who got money by it—that is to say, by printing predictions and prognostications—I know not; but certain it is, books frighted them terribly, such as Lilly’s Almanack, Gadbury’s Astrological Predictions, Poor Robin’s Almanack, and the like; also several pretended religious books, one entitled, Come out of her, my People, lest you be Partaker of her Plagues … and many such, all, or most part of which, foretold, directly or covertly, the ruin of the city. Nay, some were so enthusiastically bold as to run about the streets with their oral predictions, pretending they were sent to preach to the city; and one in particular, who, like Jonah to Nineveh, cried in the streets, ‘Yet forty days, and London shall be destroyed.’” (Daniel Defoe, 1722)

I omitted from the quotation an enumeration of books whose titles announced catastrophes and also made apocalyptic warnings urging people to flee London because the end of the known world was approaching and widespread death was advancing. Three centuries later, it is no longer pamphlets or prophets that cry out in the streets but a colossal marketing strategy of television that is dedicated as I write these words to inflaming the spirits and instilling terror day and night. Media aim to transform the last stronghold of human beings, their identity, as I describe in the first part of the triptych of this new Journal of the Year of the Plague. Apparently, a lot has changed, but not really; the media have always had a tremendous impact on the collective imagination. “The error of the times,” about which Defoe wrote in 1722, uses a different technology today, but the purpose is the same.

Triptych of the New Journal, Part I: The Invasion of the Commercial-Break-Is-All-You-Get

Like so many others, I stayed in Uruguay and almost always in Montevideo, the capital of this small Latin American nation, during these past eighteen months. I will now try to sum up in the most personal way possible the meaning of all that time from my own point of view. It is not a journalistic one, like Defoe’s, but communicational and semiotic.

Since March 2020, our life has been tightly wrapped, hermetically encapsulated in a monstrous, uninterrupted TV commercial break. Yes, the abhorrent audiovisual pollution of commercial television, which has remained an impregnable fortress to any form of dissent, debate, or mere discussion—let alone denunciation of what some of us, not so few, think that is actually happening since March 2020—besides being the longest commercial break of which I have memory in all my life. And this is particularly awful in a country where all TV channels are surely among the most bloodthirsty, when it comes to sucking massive amounts of free time, of leisure, from the people, who have no other choice but to watch their unimaginative programs. Many, way too many, are the TV shows that—besides announcing that they are “going to the commercial break,” as if they were inviting us to visit a bucolic garden, a pleasant area where we will freshen our senses—when at long last the sign appears that derisorily announces the END OF THE COMMERCIAL BREAK, there are always still more commercials to come, and when it seems that finally, the almost wholly forgotten program is going to start again, the producers use the opportunity to insert yet more advertisements. In this exploitative, savage way, commercial media have overcome the resistance to exploitation—after all, we are human—and completely defeat the audience. After breaking the will of the public, the forlorn dwellers of a grimacing, maniacal totali-authoritarian realm, accept, resign themselves, keep on keeping on, and continue exposing themselves to the toxic doses of the gargantuan commercial break that has been coming out of these infamous screens since March 13, 2020.

What I have described up to this point was the anomalous but sadly normal situation that prevailed in national television all over the country until one night in early fall 2020. After the dreadful launching of the longest national emergency ever, the already huge TV commercial break grew even longer—although it would be more accurate to say it went wild; as without missing a beat, it began invading and colonizing the last space that was still left to conquer and dominate. It did so mercilessly in all editions of all TV news programs, talk shows, and so-called journalism. Time to bid farewell to the last naïve belief that what occupies that sacred Western television slot of the central edition of the TV news is the truth and nothing but whatever story they want to tell us from 7 pm or even earlier until the wee hours in Pandemia City.

Thus, the media environment became one long ad, whose overt goal was to turn every viewer into an unthinking, submissive, and very scared citizen. Most Uruguayans succumbed to the bizarre new(ab)normal era ruled by an intrusive, relentless never-ending TV commercial break. With sadistic aggressiveness, the ever–serious-looking presenters of the three most lucrative TV channels—together with the almost identical national and municipal TV versions—plunged into a vast propaganda ocean of nothing but intense messages of sanitary alarm. The immense discharge of unrestricted advertising was launched and poured into the atmosphere in three slightly different flavors and textures:

- sweet with silky cheap pity: messages with the ever-present, necrophiliac number of casualties in the Intensive Care Unit of those who had supposedly died of/with Covid-19.

- bitter with rugged absolute scientific certainty: the utterances of the sole owners of almighty knowledge. It was delivered solemnly by never-before-seen persons who had been elevated to the throne of Definitive Science and anointed with the oil of Permanent Truth. This closed cast soon became a caste: they turned into fixtures in the studios of homogeneous Pandemic TV. They all devoted themselves body and soul to fill to the brim each of the endless, reiterated interviews to the team of scientists that advised the government and produced a growing fear of life. Media producers believed and said it was imperative to terrorize the captive audience so it could escape from the massive and inexorable death caused by the new virus.

- tutti-frutti with a coarse lucrative texture: the TV news protagonists lost all decency. They claimed with triumphalist air over and over again that they had finally defeated a very dangerous species for the survival of the channels, of those voracious eaters of free time, and of the viewers’ free will. It was a victory over the heavy user of the zapping of boredom.

There was no longer anywhere to hide from the deadly iconic spill of the new-normal. Now they could greedily count and cash in on a vast captive audience in the distressingly long winter of 2020. We witnessed the obscene gloating—like newfangled, loud nouveau riche—as they showed off their vast, perfectly still audience, made up of all those who had voluntarily locked themselves up due to the fear spread 24/7 by the media. This upshot was great for media business—not so much for those whose terrifying daily fare was a threat to their immune system. At the beginning, they succeeded thanks to their massive dissemination of a scary iconic sign of the viral evil; the news programs created an animated a version of SARS-CoV-2 in a shape resembling that of the terrifying, insatiable alien of Ridley Scott’s sci-fi film Alien (1979).

The mighty controllers of the heavily Biased-Uninformative TV news production lost all shame; it was revealed by their extreme self-assurance, by their attitude of strutting around with an air of masters of time and truth, without ever realizing this performance was scandalous. The only reason this shameless media display was not perceived for what it truly was more clearly was that is all there was offered to TV viewers. Since March 2020, no more zapping can save the newly created slaves of the only available screen because, in that fateful Year I of the Plague, the larger, freer cinema theater screen was painfully absent. If you want to be informed—the inhabitants of TVland seem to say or rather laugh with undisguised sarcasm because of their sure domination—now you must swallow your pride and mistrust as well and proceed to glue your eyes to the overheated screens from which only never-ending commercial breaks continue to uncontrollably spill over.

The relentless pandemic commercial break has been designed and disseminated inside and outside the TV studio by every reporter in the streets at all times. There is only one message from the gentle, single-minded announcer of many heads: BEWARE OF THE PANDEMIC THAT LURKS, POUNCES ON NORMALITY TO ANNIHILATE IT. COVID-19 leaves behind only the sad, new-normal bones of our former normal lives. It was the most gigantic advertising campaign of anticipation created for the new product of the twenty-first century: the salvific vaccine, which of course came in different flavors and packages. It’s all happening as if they were hawking, acting, and singing at the same time during this never-ending TV commercial break: dear customer, don’t miss the imminent launching of our star brand-new product, the one your organism absolutely needs forever! And don’t forget that it will most definitely change your lives!

That’s what I believe, that’s what I think, that’s what I feel and write now, in my own Journal of the Year of the Plague: For too long, we have been living immersed in an enormous, unbearable, ubiquitous commercial break that has encroached upon our existence, that has invaded every section of the more-popular-than-ever TV news programs as an insatiable, frantically growing tumor. There is no longer any public information that possesses even the slightest semblance of objectivity, of fair consideration of what in the external world resists opinions and ideological positions, as reality is wont to do. That is precisely what the stubborn “obsistence” does, as Peirce1 described it (CP 2.91, 1902). I propose this idea as a working hypothesis: This excessive TV commercial break can go a long way toward explaining the massive persuasion, the all-out victory over reasonable doubt without the government having to put the army in the streets. It harvested a sea of rolled-up sleeves and expectant bare arms yearning for the injectable salvation. Another sign of the inflicted defeat on the people is the submissive adoption of a humid and dirty rag, which is useless according to a number of scientists and which people had to mercilessly plant on their facial expression to the detriment of human interaction.

Only the expanded, tyrannical, and oppressive TV commercial break can account for people giving up so many fine things that we humans once enjoyed as being normal—plain and simple normal—without any deceitful adjective. Without this colossal commercial break, our pandemic Lord who art in media could not have triumphed as it did. It may be useful to understand the raging media battle for everyone’s hearts and arms to consider the symbol with which Constantine fought: In hoc signo vinces (“In this sign thou shalt conquer”). Without the holy sponsoring of the signs of the grotesque mega-commercial break that penetrated every last chink of the television (dis)information machine, the story of the greatest pandemic ever to have assaulted the Western world would not have been able to weaken and defeat immobilized humanity.

Triptych of the New Journal, Part II: An Epistle Against Altericide

What touches me the most in the open letter made public by Margaret Anna Alice under the title Letter to a Covidian: A Time-Travel Experiment?2

First, there is her timely and singular gesture of addressing the reader’s 2019 self, who had never imagined or conceived of the possibility of discriminating, persecuting, banning, and even removing from the lifeworld those who did not submit to a pharmacological treatment of little-known efficacy, whose reliability or harmlessness is most dubious in the medium- and the long-term. That was the identity of probably most of or almost the whole of mankind. Now, over a year and a half into pandemic territory, there is a large, growing collective that surveys with great zeal the rift that divides those who cherish the COVID Orthodoxy and those who doubt, who are skeptical. So many people dedicate time now to passionately watching over this rift so no undesirable human being bypasses it, so not a single unvaccinated heretic—who does not deserve compassion or solidarity—crosses it, and according to them, jeopardizes their health and threatens their sanitary existence.

I choose from Margaret Anna Alice’s open letter one of the many passages that celebrate our common, our shared humanity, that praise the conversation that turns us, imaginatively, for a time, into the other. In her open letter, she addresses her ultimate Other, when s/he was not yet one:

“I wish I could talk to your self from two years ago.… I might still be able to reason with that self. Instead, this is likely a futile exercise in trying to awaken a hostage suffering from Stockholm Syndrome to the fiendish machinations of her captor.”

This fragment brings to mind a perfect line by Uruguayan poet/songwriter Eduardo Darnauchans (1953–2007)3:

“How much I would like write a song

One that would turn me into another

Or into myself three years better.”

How we all would like to write or say something that would turn us into the persons we were almost two years ago—better, oblivious to the rift, not only freer but also willing to think a lot before accepting that our freedoms be curtailed, because once our freedoms are gone, it is a path that has no return, that mutilates our spirit forever.

What I am talking about, of course, is the time before the ghastly deep social rift was opened, the fissure the media have kept widening, full of arrogance, since they inflicted an exemplary defeat on the resistance of the viewers. To do so, they keep bringing to the studio or interviewing the same science-munching characters with the same unanimous signs countless times, enlivening the commercial break that never ends. If only we could approach that 2019 Other—without asocial distance, minus the unnatural masks, without the vacci-animation requirement, then we surely would be able to exchange normal gentle, harmonic signs with them, neither new nor old-normal—most likely we would find a common ground much closer than we suspect.

Margaret Anna Alice goes on to say, “That’s the person I want to talk to—not your present self.” I do understand her, and that’s why I now share that sentiment in my plague year journal written and endured three centuries after Defoe published his imaginative but realistic chronicle. How I wish I could find all those good people before they gave up free-thinking and succumbed to the flooding commercial-break-that-will-never-have-an-end but which masquerades as innocent, neutral, pure conveyance of news and nothing but the news.

My adult life has been dedicated to the study of media communication; I have always observed it with a mixture of fascination and fear. Now I only watch it with misgiving, even disgust: I never thought the media was going to give up any pretense of journalizing the lifeworld. I never imagined the commercial machinery of television could turn so quickly into an instrument of oppression, that it would be swiftly redesigned for the greater glory of the global powers that be.

Triptych of the New Journal, Part III: In Defense of Astonishment

A year ago, I received what seemed a mundane invitation to engage in dialogue with Uruguayan psychoanalysts about an essay written by one of their peers. However, the title of the text that summoned us, namely, “La Peste, el Otro, el Psicoanalista y Todos Nos-Otros” (“The Plague, the Other, the Psychoanalyst, and All of We-Them”)4, awakened my curiosity and hope. I was particularly curious and hopeful about two of its words: one was “plague” (peste in Spanish), an anachronistic way of referring to the pandemic, which at that time had just reached its fourth month of existence, an anniversary much celebrated in all media. I was also drawn to the coined pronoun “we-others”5 (the Spanish word for “we” was split in the middle—“nos-otros—by inserting a playful hyphen that dismembered it into the collective of identification us (= “nos”) and the word “others” (“otros”). The tiny sign “us” works as the key element in all passionate, often aggressive, even deadly expressions of identity reinforcement, such as “the nation belongs to us,” “this soccer flag represents us,” or “this religious symbol can only be used by us.” However, in the coined term of the title, “nos-otros” (“we-them”), there was also “them” (“otros”), and this sign raised a red flag regarding what was about to happen in the land of authoritarian Pandemia. It was a precious warning of discrimination, of the utter rejection of the different, of a newly felt total intolerance, of the self-indulgent pride of being incapable of standing other ideas or positions regarding the “sanitary crisis,” as the government called it on March 13, 2020.

In the new sanitary regime, there was no longer any reason for pausing and reflecting on that which we-the-majority were unable or willing to understand. Thus, the second half of “we-them” is an iconic representation of the complete separation from the Other, who is now to be judged as a criminally irresponsible person. The Other serves as the generic name for all those who just keep annoying us, the not-so-silent majority, with their senseless objections and criticism of the New Normal. Don’t they understand that it is all there is now, why do they still refuse to see we will never have another normality? Why don’t they just shut the fuck up? Those were some of the restless signs that came to my mind before I agreed to read the text I had to comment on in the virtual room where we would meet and talk late in the afternoon of July 22, 2020.

What captivated me about the essay with which I was to engage in a friendly conversation after reading it was the way its author chose to end it. That closure left me in no doubt about the vitality of the thought that had animated the writer. To me—the “me” I was in July 2020—I had come across a way of feeling and thinking that was close to my own. The author quoted, although it would be better to say she warmly embraced in her text, a well-known literary text written by Herman Melville: the perpetual answer the protagonist of Bartleby the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street gives to every request made to him: “I would prefer not to.” It is worth quoting the final paragraph, in which the author, Silvana Hernández Romillo, writes about this act of tenaciously refusing to be part of something that is not to be accepted at all:

“If even after such a long journey, in the face of a crisis or of a tormenting pain, I were asked for advice or for a word of expertise, or even, if I were asked to stay at home, I would like to always have at hand the answer of Herman Melville’s famous scrivener—‘I would prefer not to’—so as to, afterwards, continue with the dialogue, wherever it may lead us.”

In times of unacceptable health-political-media oppression, this form of resistance has a remarkable strength, and I want to thank the author of this essay for reminding me of the power of the act of asserting oneself through what Peirce describes as the fulcrum of reasoning: “The idea of other, of not, becomes a very pivot of thought” (CP 1.324, 1903). I never met the author again, neither in the scanty space of the two-dimensional digital Zoom windows nor in the vital face-to-face realm. But I would like to think the self of the person who wrote that ethically just and possibilist meditation continues to live and think in that place, that she continues to believe it is just and necessary to join the vigorous refusal of Bartleby the Scrivener to preserve our freedom, for the sake of our spirit.

And to have a dialogue with the text whose meaning I felt and thought was akin to what I thought then and what I still think today, I brought my own quote to that encounter. I resorted to a literary creation where there is another character who also refuses to submit to the majority, who says a resounding, “No, I will not give up my being, the way I am.” He did not accept joining the authoritarian herd, those who were unable to tolerate any difference and who were willing to give up their humanity, their normality, in exchange for the protection of the flock. This was the quote I used:

“I will defend myself against the whole world! I am the last man, I will remain so until the end! I am not capitulating!”

At the end of Eugene Ionesco’s play Rhinoceros (1959), thus speaks the protagonist, a man called Berenguer, who resists transforming himself into the imposing beast named in the title and joining the herd of fierce rhinoceroses, whose ominous snorts fill the air with menace. Berenguer watches them in fright while with growing noise and violence, the corpulent mammals occupy the entire city, replacing the human presence as the new dwellers of the lifeworld. At an increasingly dizzying pace, people give up their human appearance and behavior to metamorphose into formidable rhinoceroses. Even in such a dire situation, some human beings are still capable of raising this cry of resistance and tenacious allegiance to their way of being in the world.

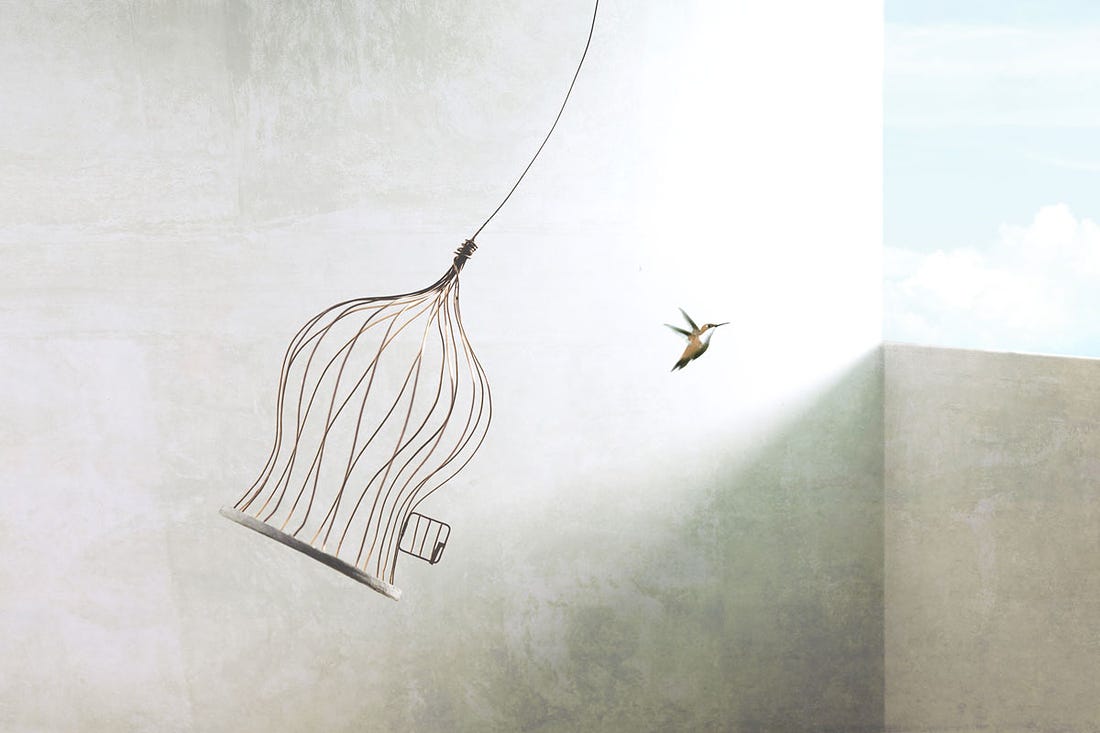

I think again of the open letter against altericide Margaret Anna Alice published, in which she expressed the same desire I feel now and which I place in this final part of this new Plague Year Journal. I do not want to give up my normality just like that; I do not want my thought to become armored, as insensitive as the thick skin of Ionesco’s rhinoceros, of the beast that invades the world and crushes everything not identical to it. If I contemplate my self today, in the spring of 2021, on the way to Year II of the Plague, I perceive it as still capable of astonishment, of feeling a tremendous jolt at each new arbitrary attack against what is free, against what truly deserves the name of normal life. Nothing else but that differentiates me.

Every other feeling and the shared story of mankind in this part of the world unite me with the Newnormal people. But I can’t help seeing how their mental epidermis becomes a little thicker every day, impregnable, a little less open to dialogical exchanges, because nothing amazes them or leaves them thoughtful anymore. Sadly, the dream of the herd has been fulfilled—but not regarding biological immunity; what I see is a herd gathered by fear and solid hatred, by the repudiation of the ones who still dare to be amazed when they hear the ferocious snorts and see a growing and enraged flock taking over the streets of life and which is unwilling to stand a single pandemic dissenter.

I close now the new Plague Year Journal with a resisting hope, which can’t help but continue seeking reasonableness—not for me alone, but for all those who can still recover that capacity for wonder in the face of the unacceptable.

Note: Should any of you wish to make a PayPal contribution in response to Fernando’s essay, please note “eXtramuros” in the Notes section, and I will donate half the proceeds to eXtramuros.

About Fernando

Fernando Andacht holds a PhD in Communication & Information from Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil; doctorate in philosophy (DrPhil) from Bergen University, Norway; MA in Linguistics from Ohio University; and Lic. en Letras from Universidad de la República, Montevideo. A Fulbright Scholar, Alexander von Humboldt Grantee, and Level II Researcher of the National System of Research, he is a full professor in the Department of Theory of the Facultad de Información & Comunicación at the Universidad de la República in Montevideo, Uruguay. Fernando performs research in the areas of media, culture, and society from a semiotic perspective. He was awarded a research grant from the Centro Nacional de Pesquisa/CNPq (2005–2007) in Brazil. In 2010, he was awarded another research grant, this time by the SSHRC (Social Sciences & Humanities Council) of Canada (2010–2013) to study the mediated representation of the real in documentaries and television. Fernando taught as a guest professor of the Graduate Program of Communication & Languages at the Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil, and the PhD Program in Semiotics at the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba in Córdoba, Argentina. He has taught in Uruguay, the United States, Norway, Germany, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Canada. Fernando has published ten books and more than 100 scholarly articles and chapters on the semiotic analysis of media and society.