by Paul Cudenec

I am very honoured to have contributed an article to the second issue of the beautifully-produced and highly interesting Parisian “counter-history” journal brasero which is being launched on Friday November 18 2022 (the first issue was reviewed in English here).

Entitled ‘For the Law of Nature: the Diggers and their heretical uprising’, my piece looks at the group of radicals who reclaimed a piece of land in Surrey during the 17th century English Revolution.

This small revolt, which still carries great historical resonance, took place in the Spring of 1649 when, as I write, “the sap of revolutionary hope was rising with the greenery of the English countryside”.

After eight years of a bloody civil war between parliament and monarchy, which left more than 80,000 dead, King Charles I had been beheaded in front of the London crowds. A republic was declared and Oliver Cromwell became head of state.

It must have felt at the time as if this was at last the victory of the people, the glorious culmination of the deeply-rooted English tradition of popular rebellions, incarnated by the legend of Robin Hood, the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 or that of Jack Cade in 1450.

This revolutionary spirit had its own name and its own references: it was the Good Old Cause, whose aim was to “win back” ancient English freedom, which was regarded as having been stolen from the people by the colonising invasion of the 11th century Normans led by William the Conqueror, whose successors were still on the throne 600 years later.

The enclosure of common land, that’s to say the privatisation of the collective inheritance by a dominant class seen as foreign and thus illegitimate, sparked uprisings at the start of the 17th century in the south-west of the country (Dorset, Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, Shropshire and Wiltshire), which spread everywhere between 1640 and 1643.

During the civil war, the poor frequently seized wheat being transported to market and shared it out between them under the noses of the owners, and peasants ripped up the hedges of the enclosures being imposed on them by the gentry.

The break-down of traditional social structures had given birth to a whole underground of forest squatters, of travelling craftsmen and workers, of jobless people, actors, wandering minstrels and jugglers, of pedlers and charlatans, of bohemians and vagabonds.

These “masterless” people gathered in autonomous zones where it was possible to live beyond the influence of church and gentry – in the forests of Dean, Pendle and Knaresborough, in Wiltshire, Cumberland, the Weald and the Fens.

Radical and even pagan religious sects flourished there and from these places emerged significant peasant uprisings at the start of the century. The virus of revolt spread out from these free zones by way of the travelling folk who roamed across the country.

Those who had lost the fight against the privatisation of common land often sought refuge in London, whose population grew rapidly, rising from 120,000 in 1550 to almost 400,000 in 1650.

Politics and religion were mostly discussed in what would now be called “the pub”, in the hundreds of taverns and ale houses of the capital city.

From this seditious scene emerged the Levellers, whose agitators played an important role in the struggle in London and, especially, in the ranks of Cromwell’s anti-royalist New Model Army.

They amounted to a kind of revolutionary avant-garde, seeking to push this unprecedented insurrection still further, and they were thus in conflict with the reformist elements of the parliamentary alliance, who sought only the modernisation of the country.

It is important to grasp that at this time England was still a second-rate global power: the British colonisation of America was barely under way. Charles I and his father James I had no interest in imperialist aspirations: they were close to the Spanish monarchy and preferred to let the Spanish empire expand without competition.

These last kings of the old order were suspicious of social change and the rise to riches of a capitalist class and thought it necessary to regulate industry, controlling wages, working conditions and industrial development.

Despite the opposition of leading manufacturers, they maintained the constraints imposed by the medieval system of guilds, associations of craftsmen which still regulated the quantity and quality of production.

The historian George Unwin, a specialist in English economic history, writes in this respect: “If such a system could have been maintained, the Industrial Revolution would never have happened”. [1]

For the merchant classes, the power of this monarchy was therefore the final barrier blocking the road to “progress” and the aim of the civil war was to tear it down.

While, outside the Leveller scene, this reformist vision largely dominated the parliamentary side in London, in rural areas dispossessed small farmers got together with small traders and market-town craftsmen to advance ideas which, in several respects, went beyond the aspirations of Cromwell and his friends.

Despite the execution of the king, sometimes regarded as a mere sop to radical sentiment, they feared that all the sacrifices made during the civil war would be betrayed by the parliamentary leaders and that the revolution would peter out.

It was in this context that, on April 1 1649, a little band of people turned up at St George’s Hill in Surrey, near Kingston-Upon-Thames. At their head were Gerrard Winstanley, a former cloth merchant turned herdsman, and William Everard, a former soldier cashiered by the parliamentary army for spreading radical material.

Calling themselves Real Levellers or Diggers, they wanted to occupy and work common land lying fallow: for them, the earth belonged rightfully to the community and all people should have the right to work and live there together.

They insisted that their initiative in Surrey was just the start of a great uprising which would turn the whole structure of English society, even the world, upside-down.

They published and circulated pamphlets across the south of England and expected to see tens, hundreds and then thousands of poor people coming to join their peaceful revolt, reclaiming what belonged to them and founding a new era.

The Diggers were aware of living at a turning-point in history, an exceptional moment of opening, when everything seemed possible. As Winstanley wrote in The Law of Freedom: “The haven gates are now set ope for English man to enter: The freedoms of the earth his due, if he will make adventure”.

The editors of brasero asked me to provide a detailed history of the Diggers’ occupation for their French readership, but since the information is readily available in English I won’t go into all the facts here.

Suffice to say that both their immediate project of digging the commons and the broader political aim of a second revolution, to break the chains of servitude in England, were crushed.

Despite an initially tolerant response to their initiative by General Sir Thomas Fairfax, commander in chief of the parliamentary army, the English ruling class used both hired thugs and its legal system to destroy their efforts, first at St George’s Hill and then at nearby Cobham.

It also smeared them, accusing them of being thugs, drunkards and even royalists seeking to restore the monarchy.

While there were similar land occupations in Wellingborough, Newmarket, Hampstead, Enfield, Hounslow, Dunstable, Iver, Barnet, Bosworth, Cox Hall and in Gloucestershire, the movement was unable to spread further in the face of repression.

With the Levellers’ leaders already arrested and the most radical regiments of the New Model Army pushed into a mutiny which was crushed by Cromwell’s troops in Burford, Oxfordshire, this spelled the end of the English Revolution.

Indeed, as historian A.L. Morton observes, the clamp-down on revolt revealed Cromwell (pictured), so happy to harness English revolutionary energy for his own ends, as in fact being “the protector of property and the friend of order”.

He adds: “This was symbolised by a splendid banquet which the City merchants gave to Cromwell and Fairfax in celebration of their victory in the Burford campaign”. [2]

What particulary interests me about the Diggers, and other radicals of the time, is the nature of the ideas that inspired them.

Many on the “Left”, including communists, have claimed Winstanley and his friends as precursors of their own movement, but the picture is not as clear as that.

Winstanley’s writings are strongly marked by a heretic and pantheistic form of Christianity, inherited from the revolutionary spirituality of the medieval Free Spirit movement and the early Protestant rebellions against the Roman Catholic Church.

It was from this traditional and pre-modern morality that he sourced his objection to the “buying and selling” that was at the rotten heart of the England being created by the victorious merchant classes.

Winstanley regarded the society he knew as a perversion of the ethical and egalitarian way of life which should have been the birthright of all and would have amounted to an extension of organic nature into the human realm.

In The Law of Freedom, he describes “the law of nature” which “does move both man and beast in their actions; or that causes grass, trees, corn and all plants to grow in their several reasons; and whatsoever any body does, he does it as he is moved by this inward law”.

And in The True Levellers Standard Advanced, he refers to “thy mother, which is the earth, that brought us all forth; that as a true mother loves all her children”.

While the vision of the contemporary “Left” is built within the framework of assumptions constructed by the system, the Diggers represented a late flowering of an old and authentic philosophical tradition which is entirely incompatible with what is termed “modernity”.

The radical pantheism expressed by Winstanley and others at the time is not some inconvenient detail to be ignored by leftists who claim them as their own, but the root source of their opposition to the transition to commercial and imperialist society that was being carried out by Cromwell.

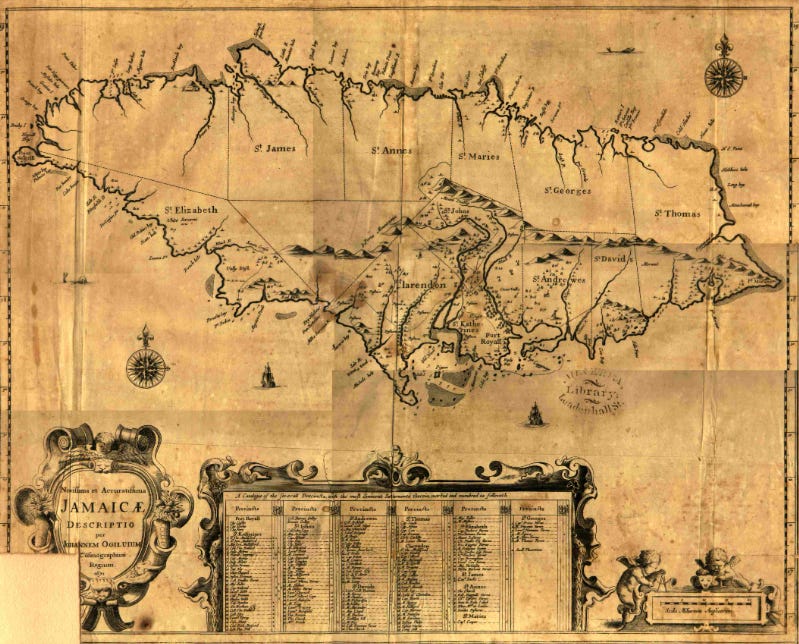

The growth of the British Empire really got under way during his rule, starting with brutal occupation of Ireland and continuing with the acquisition of Jamaica, St Helena, Surinam, Novia Scotia and New Brunswick.

It would seem that the link between the Commonwealth of the republican decade and the Commonwealth of today is more than merely linguistic!

In 1660, two years after Cromwell’s death, the monarchy was restored in “constitutional” form under Charles II and the ruling class unleashed a full-spectrum wave of repression, imposing the “law and order” necessary for a stable future for the empire and sustainable profits for the merchants and bankers who now held power.

As a side-piece to the article in brasero, I included the following personal commentary:

Surrey today has paid a heavy price for the transition to capitalism. The north of the county has become the suburbs of London, a landscape of identical houses, railway lines, roads choked with cars making endless trips back and forth between work, home, school and supermarket.

Even the south of Surrey, further from the capital, which still boasts a lush and often-protected countryside, is scarred by motorways under aircraft-busy skies.

St George’s Hill has become a very up-market area, home to financial magnates and show business millionaires. The same is true for Cobham, site of the Diggers’ second land occupation, which since 2007 has hosted Chelsea Football Club’s training centre.

I was born in Surrey, where I grew up in a modest suburb seven or eight miles away from St George’s Hill, at a time when the old British empire had collapsed and cultural confusion reigned in a society which seemed to have lost its soul and was frantically trying to find it in nostalgia – for the 1966 World Cup victory, for Winston Churchill, for Queen Victoria and her famous values, for a noble and civilising empire.

There were strikes everywhere, electricity cuts, IRA bombs, clashes on the football terraces between rival gangs of supporters and on the streets between the National Front and its opponents, as well as between the people of places like Brixton or Toxteth and the police.

Margaret Thatcher, the “iron lady”, took advantage of this anxiety by promising a return of national pride, but delivered nothing but the destruction of everything that remained of working-class communities in order to create a neoliberal desert.

I continued to dream of an England without business interests, without the State, without motorways, without hierarchy: in short, without capitalist modernity.

So on April 3 1999 I joined the march organised by The Land is Ours to commemmorate the 350th anniversary of the Diggers’ occupation.

More than 300 of us walked up St George’s Hill to erect a monument to the rebels on the former common land which is now a private golf course.

In defiance of the police, a little vacant plot next to the links was occupied in a bid to create an agricultural squat in the spirit of Winstanley and his comrades – a gesture which remained symbolic and sadly had little impact.

Rootless, disorientated and thus discontented, I never shook off the impression of having nothing to do with my native country and of belonging instead to another England which perhaps only ever existed in the parallel world of possibility.

[1] G. Unwin, Industrial Organisation in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (1904), cit. Christopher Hill, The Century of Revolution 1603-1714 (London: Sphere, 1969), p. 41.

[2] A.L. Morton, A People’s History of England (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1995), p. 217.