A nightmare totalitarian industrial world, in which everything living is being poisoned to death and in which dehumanised people are subjected to full-spectrum physical and psychological control by slave-masters they never dare question.

So here is where the modern world and its self-mythologising cult of “progress” was leading us… Who’d have thought it, eh?

The warnings have been there, of course, whether from science fiction writers and filmmakers (They Live!, The Terminator, Equals...), musicians or the dozens of thinkers featured on this website.

They warned us where this would end up if we didn’t do something, but we collectively spurned their advice and here we are, on the very brink of a long-term and probably fatal dystopia.

The important question now is how we are going to get out of this global hi-tech concentration camp.

Part of the answer is that we need to keep alive, and spread as widely as possible, a vision of how the world could be, of another way of living which is utterly different from the sterile and robotic hell currently lined up for us and those who will come after.

It is very much part of the ruling elite’s propaganda to insist that their future is the only future, that no other possibility even exists.

They are always keen to dismiss the idea of a different society as totally fanciful, empty-headed or even positively dangerous, removing us from the protective bliss of the prison they have built around us.

This lie is reinforced in people’s minds by the way that the other, possible, world is increasingly distant from contemporary reality.

It is hard to imagine a transition from where we are today (let alone where we are heading) to where many of us would like to be.

It is particularly hard, even impossible, if you go along with the ruling elite’s deliberate confusion of the passing of time with the strengthening of their industrial profit-system.

If you see “the future” as necessarily an extension of the path that has brought us from the past to the present, then their version seems inevitable. It is therefore crucial to break free from this idea of some kind of predestined vector taking us towards a hyper-industrial destiny.

Industrial capitalist development was never the only possible form which human society could have taken over the last few centuries. The shape our present has taken is not due to the passing of time but to very specific processes and actions which have occurred.

If we want to reconnect with the “other world” in our hearts, and understand why it seems so unattainable, we would therefore do well to look back at how we landed up on the disastrous path of industrialised tyranny.

A key period to analyse is the Middle Ages, when capitalism first started to take over our lives.

Silvia Federici makes some very interesting observations on this period in her book Caliban and the Witch. (1)

She rejects the conventional wisdom that a “transition to capitalism” occurred as some kind of natural social evolution.

Instead, she points out that the power of the ruling elite was being threatened by the growing confidence of the 99%, who were increasingly rebelling against authority and servitude.

With the outright slavery of the Roman Empire left behind, these medieval rebels saw ahead of them a better future, one based on social justice, freedom and local autonomy.

They were on the path leading towards the light, towards genuine social progress rather than to the fake “progress” of technological sophistication and profusion.

But this didn’t go down well with the ruling class, who feared that their power and privilege would be lost for ever.

Instead of escaping from slavery into freedom, our ancestors therefore found themselves engaged in a Great Battle for the Future with the dark forces of tyranny.

This battle raged for centuries all over Europe and in the parts of the world colonised and occupied by the dominant system.

In England the most famous uprising was the peasants’ revolt of 1381, during which radical preacher John Ball told his contemporaries that the time had come when they could “cast off the yoke they have borne so long and win the freedom they have always yearned for”. (2)

But there were plenty of others, such as the Kett’s Rebellion of 1549 in which the rebels seized control of Norwich, then the second biggest city in the country.

The 17th century radicals of the English Revolution, such as Gerrard Winstanley, represent perhaps the last flowering of this wave of revolt.

The Great Battle for the Future was even fiercer on continental Europe. As Federici points out, the uprisings of the Cathars in France and the Anabaptists in Germany were not just about isolated local grievances but represented an ideological and metaphysical challenge to the world of authority, power and property. (3)

Federici argues that capitalism was in fact the reaction of the ruling elite against their potential loss of control.

She writes: “Capitalism was the counter-revolution that destroyed the possibilities that had emerged from the anti-feudal struggle – possibilities which, if realized, might have spared us the immense destruction of lives and the natural environment that has marked the advance of capitalist relations worldwide. This much must be stressed, for the belief that capitalism ‘evolved’ from feudalism and represents a higher form of social life has not yet been dispelled”. (4)

There is a strange echo here with the 20th century, when fascism emerged at a moment when the ruling elite (by this stage firmly capitalist) again faced the threat of popular insurrection.

The parallel even extends to the way in which the medieval bourgeoisie, often depicted as leading the radical onslaught against feudal power, sought common cause with their supposed enemies in the nobility in order to stamp out popular revolt.

This same bourgeoisie, which by the 20th century liked to think of itself as “liberal“, was likewise happy to see the boot of fascism keep the rabble in their place.

Capitalism – the new form taken by malevolent ruling-class domination – subjugated our ancestors by cutting them off from their sources of subsistence and autonomy.

Common land was confiscated – enclosed – making self-sufficiency impossible. Food could no longer be freely gathered or hunted, rivers could no longer be fished, wood for fuel could no longer be picked up in the privatised forests.

People were forced into the money system, forced to earn “wages” just to live, forced into factories and workhouses, reduced to craven dependency on the capitalist system.

Federici describes the period as one of “relentless class struggle” in which “the medieval village was the theater of daily warfare”. (5)

“Everywhere masses of people resisted the destruction of their former ways of existence, fighting against land privatization, the abolition of customary rights, the imposition of new taxes, wage-dependence, and the continuous presence of armies in their neighbourhoods, which was so hated that people rushed to close the gates of their towns to prevent soldiers from settling among them”. (6)

In order to impose the New Normal of capitalism on the unwilling people, the power elite used what Federici terms “social enclosure”, (7) a precursor of today’s “social distancing”.

She writes: “In pursuit of social discipline, an attack was launched against all forms of collective sociality and sexuality including sports, games, dances, ale-wakes, festivals, and other group-rituals that had been a source of bonding and solidarity among workers”. (8)

“Taverns were closed, along with public baths. Nakedness was penalized, as were many other ‘unproductive’ forms of sexuality and sociality. It was forbidden to drink, swear, curse”. (9)

In another striking parallel with the 2020s (and indeed the 1920s/1930s) the rich elite tried to create “a new type of individual” (10) – a servile, malleable and thus profitable type.

To this end it set out to separate us from our bodies and from our very sense of who we are.

“According to Max Weber, the reform of the body is at the core of the bourgeois ethic because capitalism makes acquisition ‘the ultimate purpose of life,’ instead of treating it as a means for the satisfaction of our needs; thus it requires that we forfeit all spontaneous enjoyment of life. Capitalism also attempts to overcome our ‘natural state,’ by breaking the barriers of nature and by lengthening the working day beyond the limits set by the sun, the seasonal cycles, and the body itself, as constituted in pre-industrial society”. (11)

The communal cohesion traditionally woven by, and among, women was specifically targeted by the ruling class in their efforts to disempower and enslave the common people, says Federici.

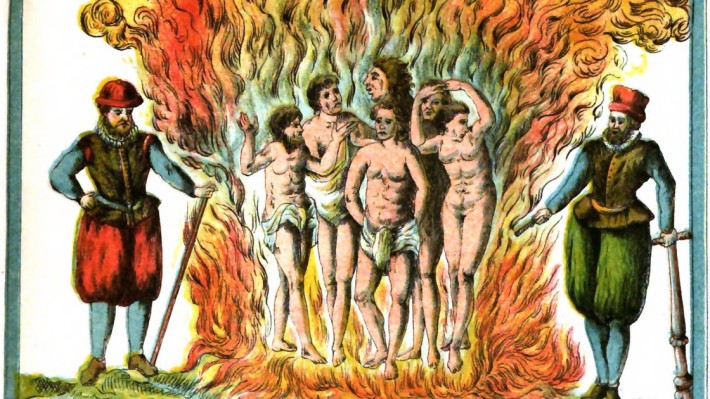

This took the form of the notorious fearmongering over “witches”, resulting in the murder of untold numbers of innocent women: “The witch-hunt destroyed a whole world of female practices, collective relations and systems of knowledge that had been the foundation of women’s power in pre-capitalist Europe, and the condition for their resistance in the struggle against feudalism”. (12)

She adds: “The witch-hunt deepened the divisions between women and men, teaching men to fear the power of women, and destroyed a universe of practices, beliefs, and social subjects whose existence was incompatible with the capitalist work discipline”. (13)

The witch hunts were thus part of the general philosophical war being waged by industrial capitalism on any way of thinking not flattened and reduced to the pitiful level of its own limited, sterile and life-hating slave-dogma.

Explains Federici: “This is how we must read the attack against witchcraft and against that magical view of the world which, despite the efforts of the Church, had continued to prevail on a popular level through the Middle Ages. At the basis of magic was an animistic conception of nature that did not admit to any separation between matter and spirit, and thus imagined the cosmos as a living organism, populated by occult forces, where every element was in ‘sympathetic’ relation with the rest”. (14)

The primary tool used by the ultra-rich minority to oppress the majority was, of course, the state.

Far from representing some kind of benign collective self-interest, as some absurdly persist in maintaining, the modern state emerged in the 14th century “as the only agency capable of confronting a working class that was regionally unified, armed and no longer confined in its demands to the political economy of the manor”. (15)

Whether claiming to be fighting “heresy”, “witchcraft” or disorder, the ruling elite deployed all the violence and propaganda of its inquisitions, wars and laws to bring the population to heel. And, as we all know to our cost, it won that Great Battle for the Future.

But because its sociopathic greed knows no end, because its “growth” is based on ever-increasing profit for the ultra-rich, it can never stop treading us further and further into the toxic industrial dust of its total control.

Today we have reached another key moment in history, when the ruling elite – under the feeble pretext of combatting a flu virus – hopes to essentially return us to the slave status we escaped a thousand years ago.

All its liberal pretence at “democracy” is going out of the window as the brutal reality of elite power becomes clear to those who have eyes to see.

There will be resistance, you can be sure of that, even if the advance disabling of certain potential sources of dissent means it may take a while for rebels to regroup and find their common voice.

Those of us who do resist will be embarking on another Great Battle for the Future.

We will be fighting for the same world of freedom and humanity and closeness to nature which inspired our ancestors hundreds of years ago.

Moreover, awareness of this historical context will be key to the way we resist.

We can never go back to the past but we can refer back to it and take our sense of direction from it.

It is clear that our defeat in the last Great Battle for the Future (and many subsequent struggles) saw us shunted down the wrong path, away from the bright future of which we dreamed and deeper and deeper into the gloom of enslavement.

We will not be able to reach our lost future by continuing along this path as it can only take us further and further from our desired destination.

The key realisation here is that industrialism, including all its technology and infrastructure, is simply an aspect of capitalism, of the slavery imposed upon us hundreds of years ago when we looked set to break free from the domination of the ruling elite.

Industrialism is not neutral. It is not something that can be turned around and used for our good. It is the prison in which we are locked.

The newnormalist technological tyranny currently being unleashed will hopefully make this inconvenient truth more evident and widely understood.

However, the underlying problem does not lie in industrialism’s excesses but in its very essence and raison d’être, as a means of control and exploitation.

We will not find the better future of which we dream in a world still polluted by factories, airports, motorways, pipelines, pylons, refineries and power stations.

The long-term happiness and self-fulfilment of humankind will not arrive via internet connections, phone networks and electricity supplies, but from their absence.

We need to destroy the whole industrial capitalist machine at the same time as we shake off this latest notching-up of repression, otherwise it will all just happen again and we will never be free.

Our victory in this 21st century Great Battle for the Future has got to be final and conclusive.

1. Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch (Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 2004).

2. Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism (London: Fontana, 1993), p. 91.

3. See also Paul Cudenec, The Stifled Soul of Humankind (Sussex, Winter Oak Press, 2014).

4. Federici, pp. 21-22

5. Federici, p. 26.

6. Federici, p. 82.

7. Federici, p. 84.

8. Federici, p. 83.

9. Federici, p. 137.

10. Federici, p. 135.

11. Ibid

12. Federici, p. 103.

13. Federici, p. 165.

14. Federici, pp. 141-42.

15. Federici, p. 84.