by Paul Cudenec

I. The trauma: corpses and tears

II. The conspirators: gold and empire

III. The means: corruption and lies

IV. The ends: profit and control

V. The future: memory and rage

I. The trauma: corpses and tears

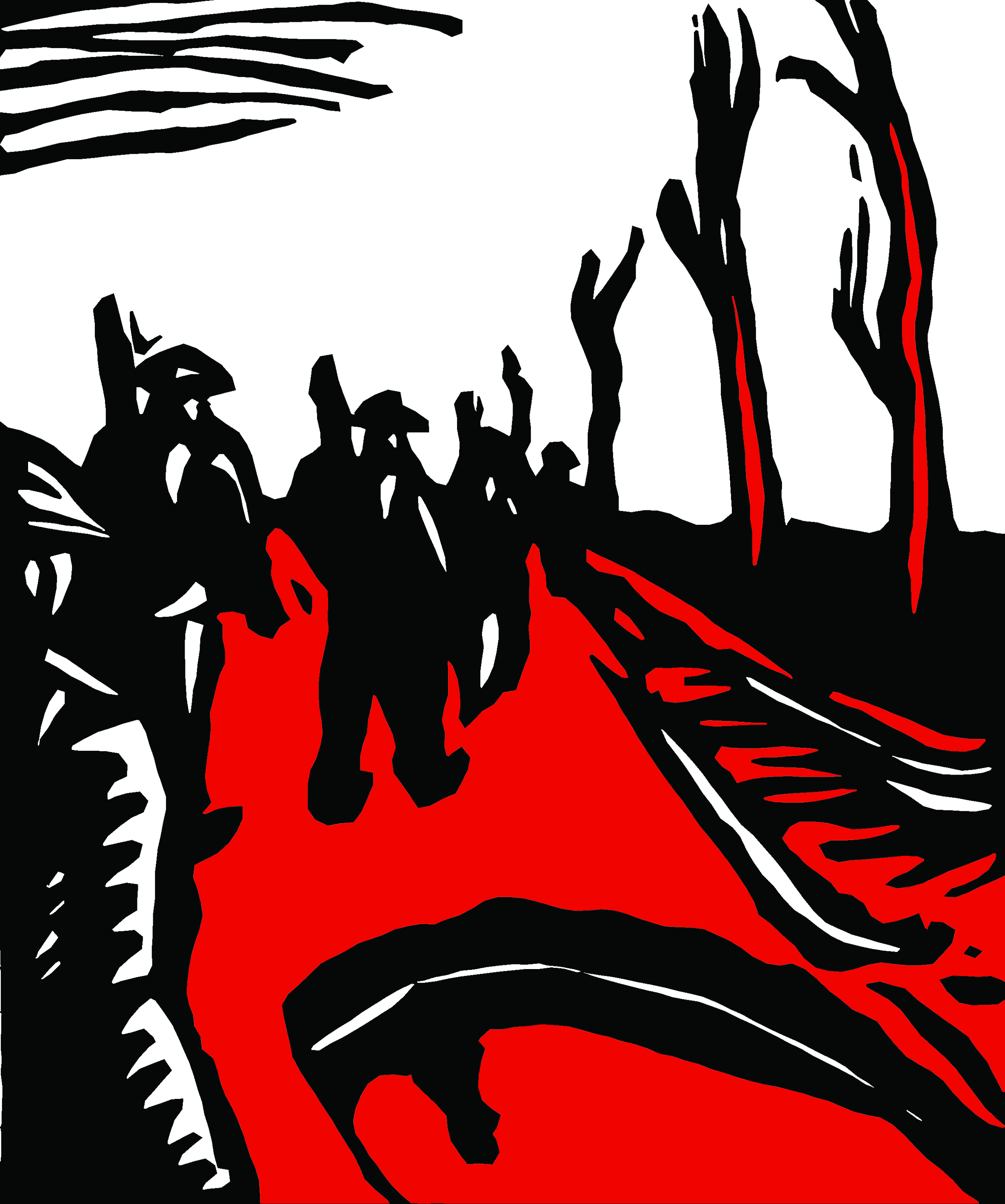

Millions of men died in the First World War, or the Great War as it was originally known, in a sickening and grotesque spectacle of mass carnage that is perhaps the closest we have ever come to bringing hell to earth.

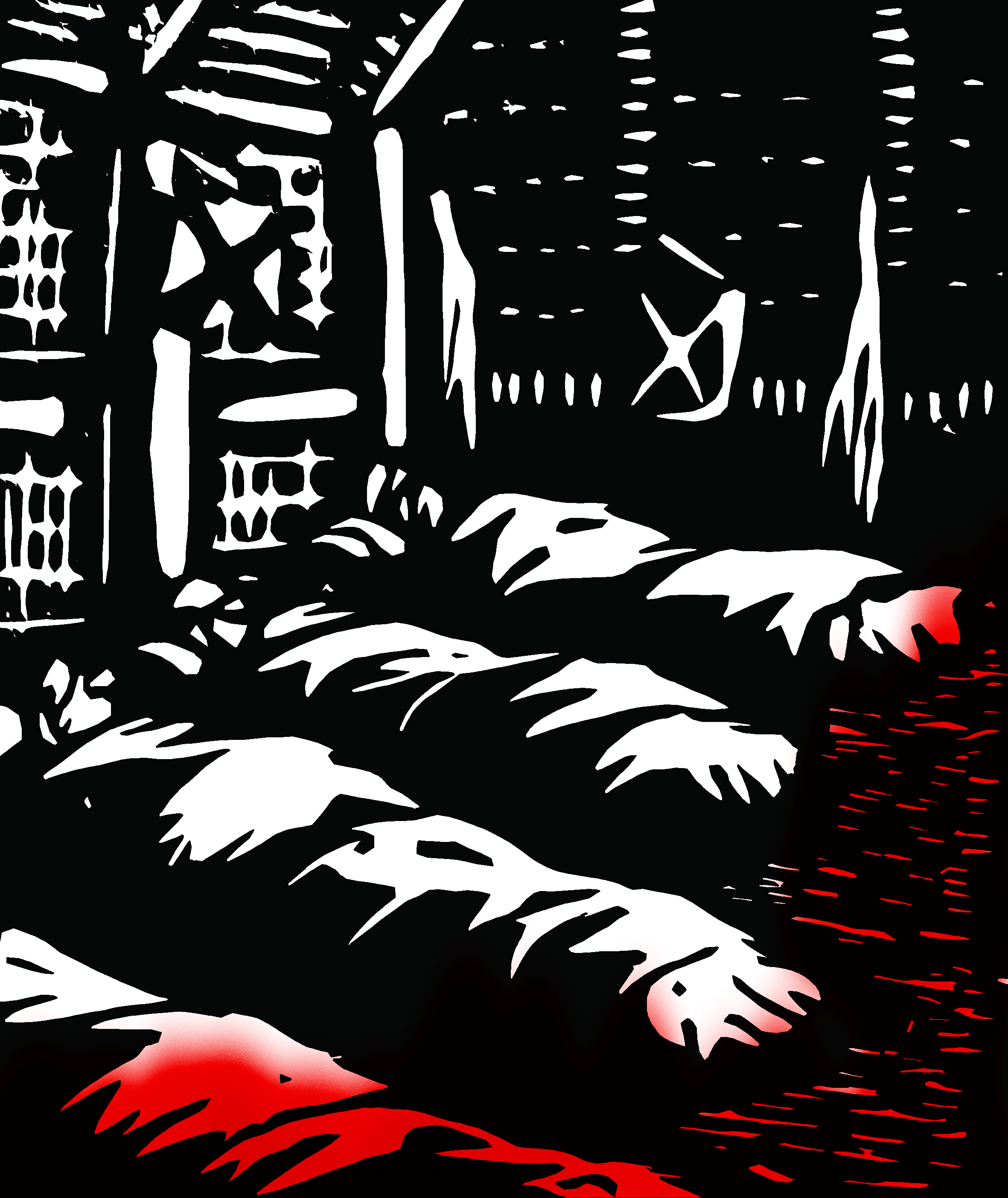

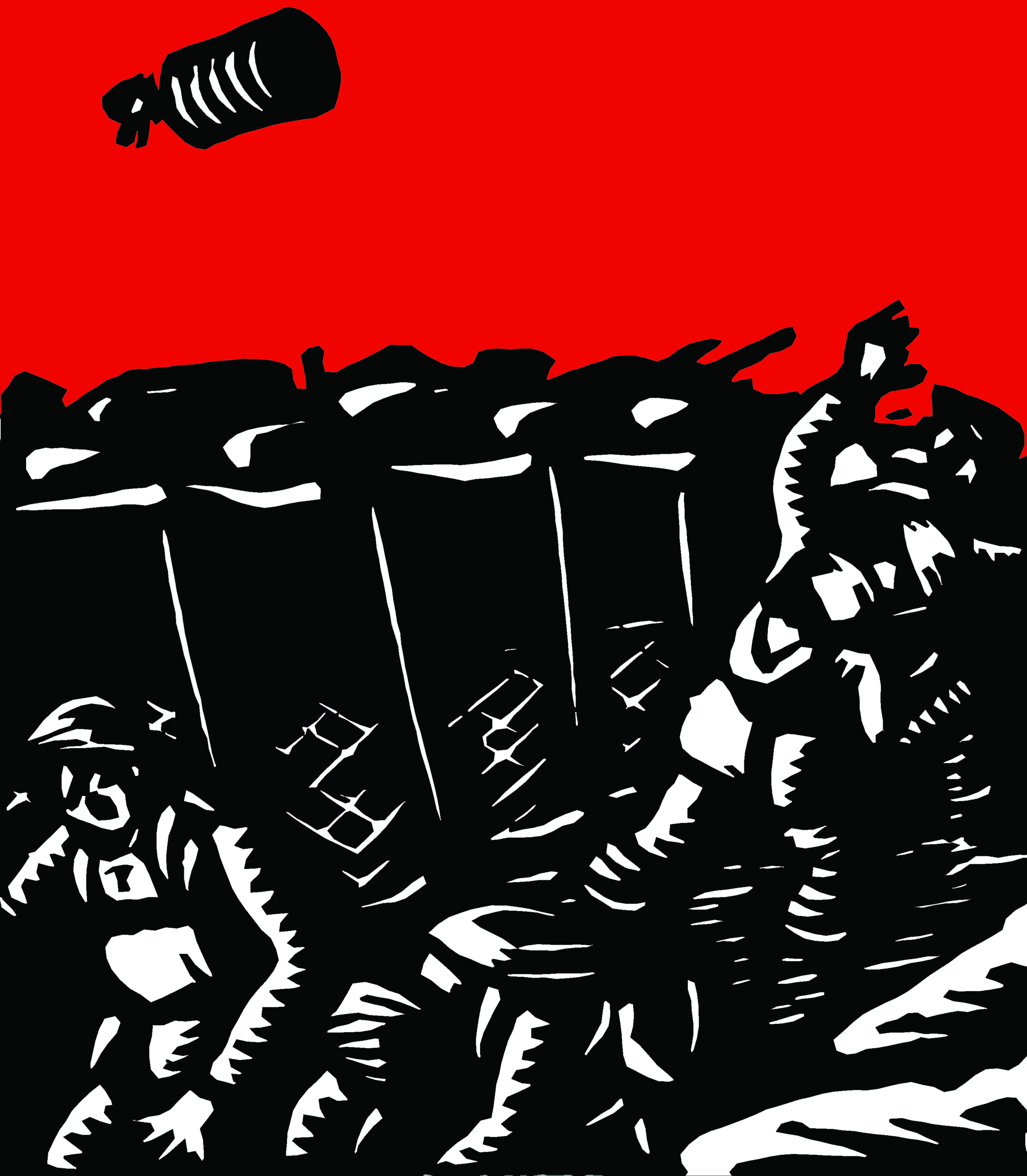

Piles of corpses, half-buried in mud and entangled in barbed wire, young bodies blown to pieces, limbs scattered in seas of blood as once again the order came to go “over the top” and advance into near-certain death in the face of shells, poison gas and machine guns.

“In the year 1916, in two battles (Verdun and the Somme) casualties of over 1,700,000 were suffered by both sides… On all fronts in the whole war almost 13,000,000 men in the various armed forces died from wounds and disease”. [1]

For years the butchery went on, while all that was gained by this odious sacrifice of humanity was a few hundred yards of territory, soon to be relinquished in the other side’s counter-attack.

Visions of the sheer horror of the trenches have haunted my imagination since I was a boy and have shaped the way I see the world.

Over the years, I have met many others of my generation who felt exactly the same way and I sometimes ask myself why this should be.

The Second World War was a much closer event and I heard first-hand accounts of the German bombing raids on England from my parents, but the First World War took place half a century before I was born. Why did it move me so much?

As a young man, I was very aware that I too would have been caught up in this nightmare had I been born at another moment in history, that it would have been me and my friends left blind or crippled or indeed wiped from the face of the Earth before we had even had the chance to live.

I wondered at times whether I had been there, in person, in some previous existence, but I now think an enormous trauma was suffered by our collective soul, which would take many years to heal.

It was above all the sheer senselessness of the killing that remained etched into the hearts of several generations.

Apart from some vague notion of stopping Prussian militarism, it was never clear to us why the First World War was even fought.

We were all aware, of course, that there were those who had profited from the war, but the event itself seemed to have been the result of chaotic clashes of conflicting national and imperial interests and ambitions; an explosion of pressure, somehow both inevitable and random, that had been building for decades and was finally sparked by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914.

How did those in power allow this absurd war to happen and carry on for so long, when the human cost was so painfully in evidence? There was a callousness there which was always hard to understand.

My later anti-war and anti-arms trade activism (during which I wrote this poem) was undoubtedly fuelled by various cultural expressions on the topic, not least the many songs that have been written on the horrors of WWI and of warfare in general (such as this one, this one, this one or this one).

One of my favourites is Eric Bogle’s Green Fields of France, originally called No Man’s Land, which is addressed to the grave of Willie McBride, a member of the whole generation that was “butchered and damned”.

And I can’t help but wonder, young Willie McBride

Did those that lie here know why they died?

And did they believe when they answered the cause

Did they really believe that this war would end wars?

The sorrow, the suffering, the glory, the pain

The killing and dying, were all done in vain

For young Willie McBride, it all happened again

And again and again and again and again

Songs like these, along with books, poems, films and artwork (like that, by William Kermode, adapted for this article) still make me cry. Tears are welling as I type these words, in fact.

These are tears not just of sadness for those who died, but of anger for those who allowed the mass murder to take place.

This anger was strong enough when I put the war down to misguided nationalism or uncaring incompetence.

But now, having read two crucially important books by a pair of Scots researchers, my lifelong sorrowful fury has found a more precise target.

In their forensically-investigated and meticulously-referenced 2013 book Hidden History: The Secret Origins of the First World War and their 2018 follow-up Prolonging the Agony: How the Anglo-American Establishment Deliberately Extended WWI by Three-and-a-Half Years, Gerry Docherty and Jim Macgregor show that the horrific butchery was deliberately planned and orchestrated in the interests of a very specific agenda.

They reveal, in their own words, that “far from sleepwalking into a global tragedy, the unsuspecting world was ambushed by a secret cabal of warmongers in London”. [2]

This network, which we might today term the military-financial-industrial complex, not only conspired to start the war, but then conspired to keep it going to fulfil its own odious aims.

I would very much recommend people read these works, along with the authors’ blog at firstworldwarhiddenhistory.wordpress.com, to gain full insight into what they have discovered.

Alternatively they could watch this excellent documentary from James Corbett which summarises their findings.

Here, I aim to make a connection which they could not do in these pre-2020 publications, nor on their website to which they last posted in 2019, and which could not be made by anyone else marking the centenary of the war’s end.

In order to do so, I will also draw on the work of historians Carroll Quigley and Niall Ferguson, both, in their own way, “insiders” granted access to archives not accessible to the general public.

That connection is obviously to the 21st century’s Great Reset, which boasts a toll of suffering rapidly rivalling that of the 20th century’s Great War and seems, chillingly, to have been organised along the same lines, with the same aims, by the same interests.

II. The conspirators: gold and empire

First of all, let’s take a look at some of the key individuals accused of having engineered the Great War.

They were all part of a publicity-shy group rooted in upper-class British society but with strong ties to what Quigley terms the “Eastern Establishment” in the USA. [3]

The driving force behind what is today called The Commonwealth, their initial wealth and influence was based largely on the looting of gold and diamonds from southern Africa.

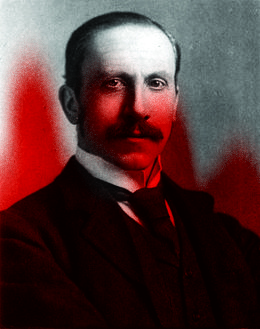

Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902)

Although he died 12 years before the war began, Rhodes played a crucial role in ensuring it took place, having initiated the creation of the secret imperialist society that planned the conflict.

The man who gave his name to Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, is today somewhat notorious, to the point that an international protest movement, Rhodes Must Fall, was set up to call for his statue to be removed from Oxford University and elsewhere.

While he has mainly been targeted for his racist views, perhaps less well-known is the extent to which he was motivated by money and power.

Quigley explains that Rhodes “feverishly exploited the diamond and goldfields of South Africa” [4] and rose to be prime minister of the Cape Colony, while journalist William Stead described him as “the first of the new dynasty of money-kings which has been evolved in these later days as the real rulers of the modern world”. [5]

Rhodes had emigrated from England to South Africa as a young man and found himself working at the Kimberley diamond fields. Write Docherty and Macgregor: “Rhodes attracted the attention of the Rothschild agent Albert Gansi, who was assessing the local prospects for investment in diamonds. Backed by Rothschild funding, Cecil Rhodes bought out many small mining concerns, rapidly gained monopoly control and became instrinsically linked to the powerful House of Rothschild.

“Although Rhodes was credited with transforming the De Beers Consolidated Mines into the world’s biggest diamond supplier, his success was largely due to the financial backing of Lord Natty Rothschild, who held more shares in the company than Rhodes himself… Neither had any qualms about the use of force against African tribes in their relentless drive to increase British dominance in Africa”. [6]

Rhodes was very close to Rothschild – in three of his wills he left the banker as his trustee, in one as his sole trustee [7] – and the two of them were founding members of the conspiratorial group, although Rothschild preferred to remain in the background.

The Rhodes Trust, with its transatlantic Rhodes Scholarships, was later to play a key role in extending the group’s influence in the USA and was part of the grand scheme for world control of which the man himself had dreamed.

Stead wrote to his wife after meeting Rhodes: “I cannot tell you his scheme because it is too secret. But it involves millions… He took to me. Told me some things he has told no other man – save Lord Rothschild”. [8]

Lord Natty Rothschild (1840-1915)

Rothschild was an extraorinarily influential international banker and financier, head of the British branch of the family and “a massive investor in gold, diamonds, oil, steel, railways and armaments”. [9]

Docherty and Macgregor note that “the Rothschild dynasty epitomized ‘the money power’ to a degree with which no other could compete”, adding that they were “all-powerful in British and world banking” and considered themselves the equal of royalty, even to the extent of calling their London base ‘New Court’. [10]

On the eve of the Great War they were “a formidable financial force”, writes Ferguson: “N.M. Rothschild & Sons was far and away the largest private bank in the City of London in terms of capital”. [11]

The family also wielded great influence in the USA through its associates at J.P. Morgan, as we will see.

On Rothschild’s death, the Western Morning News wrote: “This prince of financiers and friend of King Edward probably knew more of the inner history of European wars and diplomacy in general than the greatest statesman we have ever had. Every great stroke of policy by the nation in the last half-century has been preceded by the brief but all-significant announcement, ‘Lord Rothschild visited the Prime Minister yesterday’”. [12]

As already indicated, the financier was in on the warmongers’ conspiracy from the start; indeed even before its concrete beginning with the founding of Rhodes’ secret society in 1891. “On 15 February 1890, Rhodes journeyed from South Africa to Lord Rothschild’s country estate to present his plan”, explain Macgregor and Docherty. [13]

Alfred Milner (1854-1925)

Milner, an academic and journalist turned civil servant, took up where Rhodes had left off, pushing forward the secret group’s full-spectrum domination of the upper echelons of British life.

Says Quigley: “He became one of the greatest political and financial powers in England, with his disciples strategically placed throughout England in significant places, such as the editorship of The Times, the editorship of The Observer, the managing directorship of Lazard Brothers, various administrative posts, and even Cabinet positions. Ramifications were established in politics, high finance, Oxford and London universities, periodicals, the civil service, and tax-exempt foundations”. [14]

Milner’s connection to members of the secret conspiracy can be traced back at least to April 1891, when he is known to have dined with Rothschild. [15]

Quigley reveals that he later found lucrative employment as “confidential adviser to certain international financiers in London’s financial district”, [16] while Docherty and Macgregor note that he was “well rewarded by his banking and industrialist friends for the tireless work he did to reinstate and increase their profits”. [17]

Milner became a member of the board of the London Joint Stock Bank (later the Midland Bank), chairman of Rothschild’s Rio Tinto Co., a director of the Mortgage Company of Egypt and of the Bank of British West Africa.

Significantly, those who knew him stressed that he “believed in the highly-organised state”. [18]

He has also been cited as an early proponent of the “managerial revolution”, which is to say the control of society by an unelected group not answerable to the general public.

In both these respects we can see strong parallels between Milner’s political position and those of later controversial characters.

In Fascism Rebranded: Exposing the Great Reset, I describe the way that a post-WW2 German “management academy” was run by former members of Adolf Hitler’s notorious SS. [19]

And, of course, Klaus Schwab’s fascistic World Economic Forum started out life in 1971 as the European Management Forum.

Like Milner, Schwab spurns democracy at the expense of “agile governance” [20] and aims for the “system management of human existence”. [21]

It is essential for anyone seeking a real understanding of our society to grasp the historical continuity between British plutocratic imperialism, fascism and the current plutofascist Great Reset.

Field Marshall Jan Smuts (1870-1950)

Remembered today for his two spells as Prime Minister of South Africa and his racist defence of the apartheid system, Smuts was a key member of the conspiracy.

He went on to sit on the British War Cabinet, an inner circle formed of trusted members of the Milner entourage to direct the 1914-1918 conflict. [22]

I have written a lot in recent years about fake greens, fake anarchists and fake leftists, but Smuts is a notable example of a fake nationalist.

Originally an enthusiastic supporter of Rhodes, who even acted as his agent, Smuts suddenly seemed to turn into his fanatical opponent.

Quigley writes that this reputation as an Anglophobe enabled Smuts to rise to a position of power in the Transvaal at a very early age.

But it was a sham: “He clung to that ideal which he shared with Rhodes and Milner – the ideal of a united South Africa. All his actions from this date onward [1895] – no matter how much they may seem, viewed superficially, to lead in another direction – were directed toward the end ultimately achieved: a United South Africa within the British Empire”. [23]

His ultimate aim of a British-dominated world empire make Smuts an early example of what is now often termed a “globalist”.

During the Second World War he was already foreseeing the creation of NATO and perhaps the EU when he “suggested that a federated Western Europe be included in the United Kingdom regional bloc” [24] of a global system.

And students of the global development agenda will be interested to learn that Smuts wrote the first draft of the preamble to the United Nations Charter.

Plus many more…

Quigley goes into detail about an extraordinary number of members of the secret Rhodes-Milner network in his books Tragedy and Hope and The Anglo-American Establishment and I won’t attempt to describe them all here.

But it is worth noting the role played by the Liberal and then Labour politician Richard Haldane (1856-1928), who acted as a Rothschild legal adviser for many years [25] and whose pre-Great War programme of army reforms was “publicly endorsed” by Natty Rothschild, according to Ferguson. [26]

There was also Liberal politician Reginald Baliol Brett (1852-1930), who became Viscount Esher in 1899, and wielded enormous influence behind the scenes.

Quigley explains: “This opportunity for influencing decisions at the center came from his relationship to the monarchy. For at least twenty-five years (from 1895 to after 1920) Esher was probably the most important adviser on political matters to Queen Victoria, King Edward VII, and King George V”. [27] He ended up in charge of the physical properties of all the royal residences.

And another semi-invisible imperial manager was Lionel Curtis (1872-1955), one-time secretary to Milner. Quigley says that what Curtis thought should happen to the British Empire often turned out to be what actually happened a generation later.

For instance, in 1911 he decided that the name of His Majesty’s Dominions should be changed from ‘British Empire’ to ‘Commonwealth of Nations’. This was done officially in 1948. “Curtis, working behind the scenes, has been one of the chief architects of the present Commonwealth”, says Quigley. [28]

Later in life, Curtis became an advocate of a world state. Imperialism and globalism are but two ways of describing one insidious process.

III. The means: corruption and lies

Anyone who has researched what has been happening to us since 2020 will be well aware of the degree of pre-planning involved.

This goes well beyond the Event 201 pandemic rehearsal, or early proposals for vaccine passports or the failed “bird flu” manoeuvre of 2005/2006.

Covid was just the trigger, the starting pistol, for the very broad Great Reset which is now being rolled out in all its phases.

Various preparations for this complex transition have been underway for a long time now, with the long-term “development” agenda and the UN Sustainable Development Goals playing a pivotal role.

The same is true of the Great War, which the conspiratorial network had been carefully planning right from the turn of the century, as soon as they had completed the Boer War manoeuvre which delivered the whole of South Africa, with all its gold and diamonds, into the grasp of their empire of greed.

And part of this project was to use the human and financial resources of that same vast empire to fuel the Great War.

The British Empire at the time boasted a population of around 434,000,000, including over 6,000,000 men of military age. But it could not be taken for granted that they would be available for the planned bloodbath.

Milner therefore set about bringing what he called “the most effective pressure to bear”, [29] arranging a colonial conference in London in 1907 to try to ensure that the various dominions would obediently take part in the war.

As Docherty and Macgregor explain, he and his associates had to be sure that Australia, South Africa and the other great dominions of the Empire were ready and willing to stand shoulder to shoulder with Britain. [30]

At this conference, a plan was therefore adopted to organise dominion military forces in the same pattern as the British Army, so that they could be integrated in the case of “an emergency”. [31]

Two years later, Milner staged an Imperial Press Conference, bringing together more than 60 newspaper owners, journalists and writers from India, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the rest of the empire, plus British counterparts, politicians and military staff. [32]

The aim was to encourage support, in advance of war, for the mother country and to foster imperial cooperation in communication and military matters.

The pre-planning paid off handsomely. Docherty and Macgregor record: “In the final analysis, Canada sent 641,000 men. By 1917, it was delivering more than a quarter of the artillery munitions used by Britain on the Western Front. Over 250,000 Canadians worked in the armaments factories under the British Imperial Munitions Board. South Africa provided 136,000 fighting troops as well as enlisting 75,000 non-whites. Australia placed its navy under British command, and a total of 332,000 Australians went to war for the Empire. New Zealand provided 112,000 men, while India alone raised 1,477,000, including 138,000 men stationed on the Western Front in 1915. In general, the governments that sent colonial troops paid for them”. [33]

Great efforts were also made to ensure that the USA would be on the side of the British empire in the coming conflict.

A Round Table group was established in New York to encourage links between Westminster and Washington, and between high finance in the City of London and Wall Street. Needless to say, it was managed in secret, hidden from the electorate and went unreported in the press. [34]

The American connection was particularly needed to finance the Great War. Explain our two authors: “Wars require to be financed and cost immense sums of money. In Britain, France, Russia and Germany the national coffers were almost bare. Outrageous spending on armaments had left virtually every treasury in Europe dangerously close to empty.

“A new source of funding was required, a supply of money that could expand in line with the demand of desperate nations willing to pay handsomely for massive loans. Now that was something that a US central bank, unfettered by government control, responding to unlimited demand, could do. The Federal Reserve Act was passed in December 1913, and the seven-man board took office on 10 August 1914”. [35]

Just in time. How very convenient!

Belgium was also involved in the pre-planning. It was the German violation of its mythical “neutrality” that was lined up as the pretext for Britain’s entry into the war, so it had to be on board.

In 1912, two years before the curtain was raised, King Albert of Belgium convened a secret meeting of the Belgian parliament and disclosed that he had evidence that Belgium was in dire and imminent danger.

The Belgian army was expanded and, significantly, the National Bank of Belgium began preparations to cope with the financial emergency that war would bring.

“In utmost secrecy, they printed 5-Franc notes to replace silver coins and planned the transfer of their reserves of gold and note-making plates to vaults in the Bank of England in London”. [36]

Serbia also had to be groomed in advance for her starring role in the outbreak of war.

“The war-makers required an incident so violent, threatening or dangerous, that Austria would be pushed over the brink”, say Docherty and Macgregor. [37]

The convoluted plot to assassinate Austria’s Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo involved Serbian government officials being manipulated by Russian diplomats who were in turn being manipulated by the warmongering conspiracy: “the real sources for their slush funds could be traced back to Paris and London”. [38]

The Russian role in the desired war likewise needed to be meticulously set up well beforehand.

Because the Czar’s regime was desperately short of capital for war preparations, following its disastrous defeat in the 1905 war with Japan, cash was invested via the involvement of the French government, with the main vehicle being L’Union Parisienne, a French bank linked to the Rothschilds through Baron Anthony de Rothschild. [39]

This capital was to be used for specific war-related enterprises in Russia, such as naval construction, armaments production and railway carriages and infrastructure.

The Russian economy grew rapidly as a result and by 1914 there were almost a thousand factories in Petrograd alone, many devoted to producing armaments. [40]

Strings attached to the financing included the stipulation that the money had to be used to build and improve railway lines heading towards Germany.

Questioning why this should be so, Docherty and Macgregor conclude: “A capable railway network was a prerequisite for the mobilization of the huge Russian armies which would be critical when war with Germany was declared. Look again at the men who laid down the stipulation. International bankers. How odd, unless of course it was they who were planning the war”. [41]

It was also obviously important to have the right people in positions of power to ensure that the war advanced as planned.

There was a hitch in this respect in France, where Prime Minister Joseph Caillaux unhelpfully stepped in to stop war breaking out in 1911.

The war conspirators, say Docherty and Macgregor, “realised that they would need to take complete control of the French government”. [42]

After much manoeuvring, involving a radical paper being bought off and politicians being bribed to vote in a certain way, the uncooperative Caillaux was replaced in 1912 by the pro-war Raymond Poincaré, who also became Minister of Foreign Affairs and then, in 1913, President.

The two authors describe the corruption and engineering of public opinion which accompanied this coup as classic methods of the controlling clique.

And they detect the same process at work in the USA, where the compliant Woodrow Wilson became President in 1913 thanks to these “machinations”. [43]

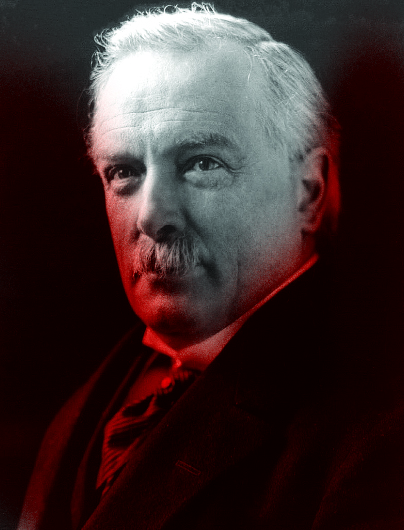

The conspirators also faced a potential problem in the United Kingdom, where the Liberal Party had swept to power on an anti-war ticket in 1908, with its fiery rabble-rouser David Lloyd George boasting real popular support.

As Docherty and Macgregor remark: “An anti-war Liberal group headed by him would have represented the Secret Elite’s gravest nightmare. The damage he could have caused was literally boundless. A splinter Cabinet led by a national figure, a rallying point for the Liberals and the Labour Party in Parliament, would have spelled disaster for the warmongers”. [44]

But there was no need for the pro-war cartel to replace him with their own man; instead they used one of the approaches I listed in this recent article and used the Welsh firebrand’s own weaknesses to bring him under control.

Lloyd George’s taste for a luxurious lifestyle beyond his means and his insatiable sexual interest in women rendered him vulnerable, explain the two authors. His career could have been ended several times over had the powers-that-be chosen to destroy him. Instead, they protected his reputation, defended him against damaging allegations and saved his career.

He had sold his soul, he was their man and the rest of his actions, including his enthusiastic support for the war, amounted to long-term payback to his powerful benefactors. [45]

You have to wonder, today as a hundred years ago, exactly how many key figures in political life are kept in line by chains of financial obligation or blackmail.

Set-ups like the Epstein/Maxwell child prostitution ring obviously spring to mind in the current context.

It is noteworthy that the influential Viscount Esher, so close to Rhodes, Rothschild and royalty, had a sexual secret that had to be hidden from the public: he had a proclivity for promiscuity with adolescent boys, which, according to his biographer, James Lees-Milne, extended to an unusual relationship with his younger son, Maurice. [46]

The involvement of the ultra-rich Rothschild clan in the warmongering group obviously made classic forms of political corruption easy to carry out.

Write Docherty and Macgregor: “The Rothschilds had amassed such wealth that nothing or no-one remained outwith the purchasing power of their coin. Through it, they offered a facility for men to pursue great political ambition and profit. Controlling politicians from behind the curtain, they avoided being held publicly responsible if or when things went wrong”. [47]

They add that the Rothschilds “frequently bankrolled pliant politicians” [48] and exercised immense influence within the leadership of both the main British political parties: “They lunched with them at New Court, dined at exclusive clubs and invited all of the key policy makers to the family mansions, where politicians and royalty alike were wined and dined with fabulous excess”. [49]

I would say that the way in which important decisions were made about the future of the country and the world in such private and exclusive settings amounts in itself to corruption.

There was no suggestion of accountability, no actual respect for the “democracy” to which these circles paid cynical lip service.

This process was amplified by the way in which the dominant clique groomed subsequent generations to take over the administration of its ill-deserved and ill-deployed power.

While today we have the WEF’s Young Global Leaders project and a plethora of other similar schemes (see here), a century ago there was “Milner’s Kindergarten”.

Docherty and Macgregor report: “Alfred Milner organized and developed a talented coterie of Oxford graduates inside his South African administration, men who by 1914 held critical positions of power in the City, the Conservative Party, the Civil Service, major newspapers and academia… ‘Milner’s Kindergarten’, the men who rose to high office in government, industry and politics”. [50]

Milner and his accomplices made an art form out of identifying potential talent, putting promising young men into positions that would serve their future ambitions and “slowly wrapping them in the warmth of Establishment approval and ultimate personal success”, [51] they say.

These men became agents of the controlling clique, without necessarily ever knowing exactly what powerful interests they served. They perhaps imagined they were merely dutifully serving their King, which was true in a way…

Many people in Britain and beyond were shocked to discover that Klaus Schwab’s Great Reset was officially launched in 2020 by the man who is now King Charles III.

But we have witnessed the same phenomenon before, as his predecessor, King Edward VII, played a leading role in the political machinations leading to the Great War, even though he died in 1910.

He engaged with political and social circles that the warmongers sought to influence, explain Docherty and Macgregor. He was their “principal ambassador, bringing to fruition plans devised in the great country houses and clubs of England”. [52]

The influence of Viscount Esher was obviously a key factor, but Edward was also very good friends with another member of the conspiratiorial group, namely Lord Rothschild.

Ferguson reveals that Natty Rothschild had been introduced to Edward, then the Prince of Wales, in 1861.

This was a “real social breakthrough” [53] for the banking family, who were able to become an integral part of Edward’s social circle.

Add Docherty and Macgregor: “Encouraged by their ‘generosity’, the prince lived well beyond his allowance from the Civil List, and Natty [Rothschild] and his brothers, Alfred and Leo, maintained the family tradition of gifting loans to royalty.

“Indeed, from the mid 1870s onwards, they covered the heir to the throne’s massive gambling debts and ensured that he was accustomed to a standard of luxury well beyond his means”. [54]

They say that both the great estates of Balmoral and Sandringham, so intimately associated with the royal family, were facilitated, if not entirely paid for, through the largess of the House of Rothschild. [55]

Obviously this was not something their adoring subjects were meant to know about and so, as Ferguson remarks, the Rothschilds’ “gift” of the £160,000 mortgage (around £11.8 million today) for Sandringham “was discreetly hushed up”. [56]

Edward led a debauched life. He apparently visited the most luxurious brothel in Paris, Le Chabanais, so often that his personal coat of arms hung above the bed in one of the exclusive rooms. [57]

But this was not so much kept quiet as used for cover. “He was shielded from public awareness of his political machinations by the very playboy image he so readily embodied”, [58] comment Docherty and Macgregor.

Whether deliberately or not, the image of a bumbling, traditionalist, nature-loving Prince of Wales has served in the same way to hide the real political role of the present incumbent of the British throne!

The mind-boggling unanimity with which every great institution fell in line with the Covid propaganda, along with its New Normal, Great Reset and Build Back Better agenda, has opened a lot of people’s eyes to the reality of power in the 2020s.

Religious leaders, not least the Pope, have very much been part of this phenomenon and the Church in Britain also played an important and shameful role in cheerleading for the slaughter in the trenches of the Great War.

Leading academics at Oxford University claimed that Britain and her Empire were fighting for “the supreme interests of Christian civilization”. [59] The concept of a Christian duty to fight was virtually universal among the Anglican clergy. [60]

The Bishop of London, Arthur Winnington-Ingram, claimed to have added ten thousand men to the armed services with his sermons and other recruiting crusades.

After a year of war, he called for the men of England to “band in a great crusade – we cannot deny it – to kill Germans. To kill them, not for the sake of killing, but to save the world; to kill the good as well as the bad; to kill the young men as well as the old; to kill those who have showed kindness to our wounded…” [61]

He later wrote: “This nation has never done a more Christ-like thing than when it went to war in August 1914… the world has been redeemed again by the precious blood shed on the side of righteousness”. [62]

There seem to have been very material considerations behind this cruel inversion of the teachings of Jesus Christ by the Church of England. Docherty and Macgregor note that “many of their senior churchmen held shares in the armaments industries”. [63]

From Kosovo to Kiev, “humanitarian” excuses are often provided for military engagements and massive dubious transfers of money.

Docherty and Macgregor do a great job in explaining how, in the First World War, aid to Belgium amounted to “one of the world’s greatest con jobs”. [64]

In short, the narrative was that the Belgian people were at risk of starvation under German occupation, which wasn’t really the case, and that therefore supplies had to be sent to help them.

Not only did certain people rake off a lot of profit from this scam, but it also allowed much of Belgium’s own home-grown produce to be sent back to Germany, where a starving population would have forced the Kaiser to seek an end to the conflict.

This way, the lucrative war show was kept rolling for a few more years.

The Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB) hailed itself as “the greatest humanitarian undertaking that the world had ever seen”. [65]

It later claimed to have spent over $13,000,000,000 on relief for the people of Belgium, a truly staggering figure for the period. [66]

The man in charge was Herbert Clark Hoover, later the 31st President of the United States, whom the two authors do not hesitate to describe as “a confidence trickster and a crook”. [67]

With a certain inevitability, it turns out that he was deeply connected to the circles that had planned the very disaster which he was now allegedly alleviating.

“The American-born mining engineer lived in London for years and was a business colleague of the Rothschilds. He was a friend of Alfred Milner… He had assisted Alfred Milner in South Africa. He held shares in the Rothschilds’ Rio Tinto Company and was associated with the same all-powerful Rothschild dynasty which invested in his Zinc Corporation”. [68]

“When Herbert Hoover negotiated the massive loans for Belgian Relief from Allied governments he used the J.P. Morgan organizations in America, co-ordinated through Morgan Guaranty Trust of New York which, in turn, made the requisitve transfer to London”. [69]

“Hoover was fearless in overspending other people’s money. By mid-1916 the commission’s expenditure in Belgium exceeded its income by $200,000 a month, but Hoover knew that he would be able to source the funding for the simple reason that it was planned… Financial muscle was never far from his center of power. The Morgan/Rothschild axis was wrapped around the entire project”. [70]

Phoney morality, of the kind preached by the pro-war churchmen or cynically exploited by warmongering “humanitarians” and “philanthropists”, has been very much in evidence in the 2020s, as voices from all sides insist that everyone has an ethical duty to wear a mask, obey orders, get the jab and unquestioningly believe the narrative.

Shame has been brought to bear on those who fail to comply – directly from official messaging and indirectly from family, friends or colleagues who have fallen for the manipulation.

In the Great War, shaming was likewise used against dissenters. White feathers were widely handed by women to men who declined to volunteer for the mass slaughter and were therefore branded “cowards”.

Anti-war activist Fenner Brockway later said he had received enough white feathers to make a fan!

The white feathers were not, needless to say, a spontaneous pro-war gesture on behalf of the women of Britain, inexplicably eager to lose sons, brothers, husbands, boyfriends and future dreams to the hell of the trenches.

In this article, Nicoletta F Gullace reveals that the shaming initiative was launched by Admiral Charles Penrose Fitzgerald.

This inveterate conscriptionist was a disciple of Lord Roberts, himself an associate of Rhodes and Milner who had been involved with their activities in South Africa. [71]

On August 30, 1914, the imperialist admiral deputized thirty women in Folkestone, Kent, to hand out white feathers to men not in uniform.

He warned the men of the seaside town that “there is a danger awaiting them far more terrible than anything they can meet in battle,” for if they were found “idling and loafing tomorrow” they would be publicly humiliated by a lady with a white feather.

One of the most painful aspects of the Covid scare for me was the way in which people on the left, even supposed anarchists, suddenly abandoned all criticism of the state, the media and Big Pharma and used the weight of their supposed moral high ground to shame those of us who had seen through the scam.

In researching the white feather campaign, I discovered that an eerily similar thing happened at the outbreak of the Great War.

Suffragettes Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst and their Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) had spent the decade before the war attacking the British state in the name of women’s rights, using direct action tactics that shocked public opinion at the time.

However, shortly after the outbreak of the war, the Pankhursts carried out secret negotiations with the government and, on August 10 1914, the British state announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison.

In return for agreeing to stop their militant activities, reveals this article, “the WSPU was promptly awarded a grant from the government for the sum of £2,000 (not an insignificant amount back then).

“Emmeline Pankhurst also declared her support for the war effort and began to demand military conscription for men (which was not introduced until 1916).

“Furthermore, the suffragettes were among those who handed white feathers to males not in uniform, including teenage boys as young as 16.

“Mrs. Pankhurst toured the country, making recruiting speeches. Her supporters handed the white feather to every young man they encountered wearing civilian dress”.

In October 1915, the WSPU even changed its newspaper’s name from The Suffragette to Britannia!

Emmeline Pankhurst’s new-found enthusiasm for the British state was reflected in the paper’s new slogan: “For King, For Country, for Freedom”.

Daughter Christabel demanded the “internment of all people of enemy race, men and women, young and old, found on these shores”.

In 1917 this pair of Pankhursts formed The Women’s Party with a programme which echoed the warmongering conspiracy’s agenda by calling for “a fight to the finish with Germany”.

In this article, Gullace comments that the WSPU had “turned itself into a junta of pro-war militants, distinguished by an enthusiasm for war that rivalled the radical right.

“Indeed, the confluence between the ideology of the WSPU and the actions of the white feather girls was so striking that Christabel Pankhurst’s pacifist sister, Sylvia, even surmised that the two groups were one and the same”.

A second reason for the British state to fund these pseudo-radicals’ activities was that they were “useful in helping to break down union resistance to women filling the roles left by men in the workplace”.

“The Pankhursts sponsored gigantic parades demanding female admittance to union jobs, while engaging in a theatrical strike-breaking campaign in the North, where they argued that women workers would never ‘down tools’,” writes Gullace.

John Simkin notes that Christabel and Emmeline ended up completely abandoning their apparently left-wing beliefs and “advocated policies such as the abolition of the trade unions”.

As with the activities of the contemporary “Pfizer Left”, the warmongering and shame-dispensing Pankhursts were part of a two-pronged assault on dissent.

The British state took its own kind of direct action against the likes of Brockway, recipient of so many white feathers: the offices of the Labour Leader, which he edited, were raided in August 1915 and he was charged with publishing seditious material.

In 1916, Brockway was again arrested, this time for distributing anti-conscription leaflets. He was fined, and after refusing to pay the fine, was sent to Pentonville Prison for two months.

Like the Covid crisis, the Great War was used as a general excuse to ramp up state control and clamp down on ordinary people’s freedom.

The Defence of the Realm Act was amended and extended six times over the course of the war to give the government powers “close to those enjoyed by a military court martial in a dictatorship”. [72]

Meanwhile, the Munitions of War Act of 1915 imposed unprecedented control over workers and introduced draconian limitations on their rights.

Factories could be declared “Controlled Establishments” in which no wage increases were allowed without the state’s consent.

Strikes and lockouts were outlawed. Workers could no longer move from one part of the country to another without explicit permission and were obliged to take certain jobs and work overtime, paid or unpaid. [73]

As Docherty and Macgreror remark, this loss of liberty had to be justified by “cleverly staged propaganda”. [74]

The “lies and deceit” [75] formed an essential part of what Quigley describes as the overall picture of “censorship, propaganda, and curtailment of civil liberties” [76] – and these sinister outlines are all too familiar to us today.

This manipulation of public opinion started as soon as the Boer War ended and the warmongers’ next objective came into sight.

“A massive and consistent propaganda drive was needed to create a German ‘menace’ and whip the British people into a froth of hatred towards Germany and Kaiser Wilhelm”, [77] write the two authors.

“In 1906, the British electorate had voiced an overwhelming desire for peace and substantial reduction in spending on armaments, but the Secret Elite turned pacifism on its head through an age-old weapon: fear.

“Fear was required to stir the complacency of Edwardian England and counter the anger of workers on poverty wages evidenced in strikes and walkouts in mines, factories and shipyards across the land.

“Fear generates doubt and suspicion. Fear is the spur that has the masses demanding more and more weapons to defend homes and families, towns and cities. It has always been so”. [78]

Fear and suspicion. It does indeed appear that the same methods and devices are rolled out time and time again to help advance a certain nefarious agenda.

Taking control of the media was then, as it has been since, an important element of the conspirators’ pre-planning.

The Times was not the most widely-read newspaper in Britain but it certainly wielded the most influence on those in positions of power.

Quigley considers that although Milner’s associates did not actually own “The Thunderer” until 1922, they clearly controlled it as far back as 1912 and that it had probably been safely in the hands of those circles since 1884. [79]

He adds that Encyclopedia Britannica was, in turn, controlled by The Times, [80] which presents some interesting parallels with its contemporary equivalent, Wikipedia.

Propaganda had already been deployed in the Boer War, which was dressed up as a defence of British settlers’ rights against Boer oppression, rather than as the grab of gold resources that it really was. [81]

Now, censorship and propaganda were employed together to simultaneously conceal all accounts of wrongdoing or mistakes by Britain and its allies and to publicise, exaggerate or invent stories of atrocities or dastardly plans by the German and Austro-Hungarian enemy. [82]

In August 1914 Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, announced the formation of an all-powerful press bureau with the purpose of providing “a steady stream of trustworthy information supplied both by the War Office and the Admirality… to keep the country properly and truthfully informed from day to day of what can be told, and what is fair and reasonable; and thus, by providing as much truth as possible, exclude the growth of irresponsible rumours”. [83]

Trustworthy information, as much truth as possible, countering irresponsible rumours. The similarities to the 2020s Great Reset would be amusing if they were not so alarming.

Famous academics and novelists also became willing cogs in the sophisticated propaganda machine [84] as the media, in Britain and France, obediently and enthusiastically toed the official line and peddled state propaganda, with the usual outrageous distortions which have now became so familiar.

When the Lusitania, a liner used for transporting munitions, was sunk by a German U-boat, The Times announced that “four-fifths of her passengers were citizens of the United States”, while the actual proportion was 15.6 percent.

And a French newspaper published a picture of the crowds in Berlin at the outbreak of war in 1914 as a picture of Germans “rejoicing at news of the sinking of the Lusitania”. [85]

In the USA, newspaper editors and owners played an important role in turning public opinion there in favour of involvement in the European war.

The corrupt machinations that made this possible were exposed by Congressman Oscar Calloway of Texas, who placed a damning statement on the Congressional Record on February 9, 1917.

He revealed that in March 1915 “J.P. Morgan interests, the steel, shipbuilding and powder interests and their subsidiary organizations” had employed 12 men high up in the newspaper world to assess the influence of more than 170 newspapers across America.

These had come to the conclusion that by buying 25 of the most famous titles, they could control public opinion.

The plan went into action, thanks to Morgan money, and a compliant editor was placed in each paper to supervise and edit the so-called “news”. [86]

All conspiratorial activity depends for its success on its victims not being aware of what is being done to them.

As well as feeding them false and misleading information, it is obviously of great importance to stop them learning the truth.

This was already true of the network in general and why they chose the form of a secret society to advance their agenda.

Quigley’s assessment is that “this organization has been able to conceal its existence quite successfully, and many of its most influential members, satisfied to possess the reality rather than the appearance of power, are unknown even to close students of British history”. [87]

As far as the specific war issue was concerned, this need was even more pressing. As Docherty and Macgregor stress: “Had the public known of their intention to manipulate a war with Germany, the government would have been swept from office”. [88]

Manufactured hysteria over “German spies” in the build-up to war was used as an excuse to create intelligence agencies MI5 and MI6 [89] and at the same time the Official Secrets Act was brought in: the common aim was to protect the war conspirators from public scrutiny and exposure.

During the war, whisteblowers were silenced. Docherty and Macgregor detail how Captain Turner of the Lusitania, whose account of the sinking differed from the official version, “was subjected to a concerted legal attack from the British establishment” [90] and suggest that famous nurse Edith Cavell was killed at the behest of the gang because she was about to blow the whistle on the “aid” scam to Belgium. [91]

After the war, there was the need to destroy all evidence of what had really happened. “Had the truth become widely known after 1918, the consequences for the British Establishment would have been cataclysmic”, [92] say the two authors.

Most of the official records of the Admiralty, Foreign Office and Board of Trade were removed, presumed destroyed. [93]

In the early 1970s, Canadian historian Nicholas D’Ombrain noted that the War Office records had been “weeded”, with as many as five-sixths of “sensitive” files removed as he pursued his research. [94]

Diaries and memoirs have been censored and altered, evidence sifted, removed, burned, carefully “selected” and falsified. [95]

Ferguson laments that Natty Rothschild’s order that all his correspondence be destroyed after his death in 1915 resulted in there being little for him to examine in the Rothschilds’ own archives, “leaving the historian to wonder how much of the Rothschilds’ political role remains irrevocably hidden from posterity”. [96]

Most extraordinary is the story of how hundreds of thousands of important documents concerning the origins of the Great War were hoovered up across Europe and deposited in the locked vaults of Stanford University in the USA.

“Hoovered” is very much the right term, as the man in charge of the operation was Herbert Hoover, fresh from his fake-humanitarian exploits in Belgium.

He was now presented as a scholarly individual who “loved books” and wished to collect manuscripts and reports relating to the war because they would otherwise “easily deteriorate and disappear”. [97]

Despite having no official permission to do so, he employed teams of men, in their army uniforms, to snoop around official archives everywhere and steal as many documents as they could.

The first haul of this “Great Heist” amounted to 375,000 volumes of the “Secret War Documents” of European governments, according to the New York Times. [98]

How Hoover’s organisation managed to pay more than 1,000 agents for this task remains a mystery. His declared “donation” of $50,000 would have paid for only around 70 of them for a year. [99]

Docherty and Macgregor devote a 500-page book to describing how the warmongers conspired to prolong the “narrow window of opportunity” (to use Klaus Schwab’s apposite 2020 phrase) represented by the Great War.

“War was a source of profit that benefited them all, and the longer it lasted, the greater that profit”, [100] and so “every action they took deliberately prolonged the war”. [101]

The war could have been over in 1915, they argue, but it was stretched out at the cost of millions of lives.

An early end did not bear contemplation for the manufacturers whose investments in new plants, new infrastructure and expanded capacity was predicated upon several years of conflict.

“The profiteers had initially bought into procuring the loans and providing the munitions because they had been promised a long war”. [102]

The authors even make a good case that Lord Kitchener, in favour of ending the war with a fair peace, was deliberately killed, along with 700 others, at Scapa Flow in 1916. [103]

The supposed British naval blockade of Germany between 1914 and 1916 was “a cruel charade that was designed to fail”, [104] they say, and didn’t even stop the transatlantic supply of gun cotton for the German howitzers. [105]

Oil supplies were maintained to Germany, notably via the Steaua plant, which by 1914 had become the largest and most productive installation in Romania.

Again, there is a link to members of the warmongering network, explain the authors.

Steaua’s success had only been achieved through sourcing vast sums of money, “and much of that investment came from the Rothschilds”.

“In due course Deutsche Bank appointed a friend and colleague of the Rothschilds, Emil von Stauss, to manage the Steaua Romana Company. He was Managing Director of the Rothschild/Nobel/Deutsche Bank oil consortium, the Europaische Petroleum Union (EPU).

“Thus, in the pre-war years, a strategy emerged to guarantee Germany’s future oil supplies, under the benign direction of the Rothschilds”. [106]

IV. The ends: profit and control

Having looked at the means by which the conspirators engineered and prolonged the war, and successfully hid their activities from the public, we now come to the question of why they did so.

As will already be apparent, short-term monetary gain was a significant factor.

During the current Great Reset, there have obviously been massive profits to be made for businesses prepared in advance to sell masks, plastic screens, signage, various online services and “vaccines”.

During the last century’s Great War, the most obvious and immediate source of profit was by the arms trade.

Most people at the time would have imagined the businesses involved to be independent firms, competing for government contracts.

But this was not true and they in fact formed a monopolising ring based, in Britain, around Vickers Ltd; Armstrong, Whitworth and Co Ltd; John Brown and Co Ltd; Cammell, Laird & Co, and the Nobel Dynamite Trust.

Write Docherty and Macgregor: “The ring equated to a vast financial network in which apparently independent firms were strengthened by absorption and linked together by an intricate system of joint shareholding and common directorships.

“It was an industry that challenged the Treasury, influenced the Admirality, maintained high prices and manipulated public opinion”. [107]

There were some at the time who saw through their game. Lord Welby, former permanent secretary to the Treasury, warned: “We are in the hands of an organisation of crooks. They are politicians, generals, manufacturers of armaments, and journalists. All of them are anxious for unlimited expenditure, and go on inventing scares to terrify the public and to terrify ministers of the Crown”. [108]

After the war, in 1921, a sub-committee of the Commission of the League of Nations concluded that arms firms were guilty of promoting and profiting from war, bribing government officials both at home and abroad, and swaying public opinion through the control of newspapers. [109]

Were our war-planning conspirators part of this arrangement? Ferguson states: “There is no doubt that the Rothschilds had their own economic interests in the rearmament”. [110]

In 1888 the London Rothschilds issued shares worth £225,000 for the Naval Construction and Armaments Company and later issued £1.9 million of shares and debentures to finance the merger of the Maxim Gun Company with the Nordenfelt Guns and Ammunition Company. [111]

Natty Rothschild “retained a substantial shareholding in the new Maxim-Nordenfelt company and exerted a direct influence over the firm’s management”. [112]

At the same time, the Austrian Rothschilds also had an interest in the enemy’s war machinery, with a substantial stake in the Witkowitz ironworks, supplier of iron and steel to the Austrian navy and later of bullets to the Austrian army. [113]

Little surprise that Lord Rothschild “vehemently supported” [114] increased defence spending before the war or that, as Ferguson reveals, “he remained an enthusiast for naval construction even when it was obvious that the costs were likely to lead to higher taxes”. [115]

Once they had successfully launched the Great War, the arms trade and its friends wanted to make sure it kept going.

Lloyd George had essentially written them a blank cheque and promised that the British taxpayer would cover whatever the cost of extending production lines or constructing new factories, irrespective of how long the war lasted.

Note Docherty and Macgregor: “He committed the government to compensate them and any of their sub-contractors for any subsequent loss. The War Office protocols to protect the public purse were torn to shreds”. [116]

Every shell fired on the front line represented another transfer of money from the public purse to the arms industry.

So the guns had to keep firing and the young men had to keep dying in the interests of the arms trade’s sustainable prosperity.

The notorious Battle of the Somme of 1916 saw almost two million shells fired over six days at German positions before the infantry attack.

It was a failure. But, comment Docherty and Macgregor, “you might even believe that it was a striking victory if viewed in terms of the profligate use of munitions rather than the awful carnage and wasteful sacrifice of mutilated armies”. [117]

“War is a racket,” wrote Major General Smedley Butler of the United States Marine Corps. “It always has been. It is possibly the oldest, easily the most profitable, surely the most vicious. It is the only one international in scope. It is the only one in which the profits are reckoned in dollars and the losses in lives.

“A racket is best described, I believe, as something that is not what it seems to the majority of the people. Only a small ‘inside’ group knows what it is about. It is conducted for the benefit of the very few, at the expense of the very many. Out of war a few people make huge fortunes”. [118]

Expert racketeers, whether their subject is war or a fake pandemic, make sure that they benefit in multiple ways from their scam.

It wasn’t just the arms firms themselves that grew fat from public spending on war. All the businesses supplying the conflict, not least the oil industry, amassed huge profits from the 1914-1918 conflict.

But the racket didn’t even stop there. There was vast “value” to be created from the financing of death.

Quigley is forthright in his description of the role played by international bankers: “The outbreak of war in 1914 showed these financial capitalists at their worst, narrow in outlook, ignorant, and selfish, while proclaiming, as usual, their total devotion to the social good”. [119]

“The attitudes of bankers were revealed most clearly in England, where every move was dictated by efforts to protect their own position and to profit from it”. [120]

He explains that the dominance of these investment bankers was based on their control over the flows of credit and investment funds through bank loans, the discount rate, and the rediscounting of commercial debts; they could dominate governments by their control over current government loans and the play of the international exchanges. [121]

The gold standard was generally suspended at the outbreak of war, thus removing the automatic limitation of the supply of paper money.

This meant that the banks were able to lend unlimited amounts of money to governments to pay for the war, without having the gold to back up the money.

“The creation of money in the form of credit by the banks was limited only by the demands of its borrowers”, writes Quigley. [122]

Obviously these loans would all have to be paid back later, plus interest…

The primary winner from the financing of many aspects of the Great War was undoubtedly J.P. Morgan, based in New York but with close ties to the City of London.

In January 1915, the British Treasury appointed John Pierpoint Morgan as its sole purchaser in the United States, thereby handing him control over the spending of thousands of millions of British tax-payers’ pounds. [123]

His agents controlled the orders for steel and armaments, for cotton, wheat and meat, for the transportation of these goods across the Americas and the maritime fleets that crossed the oceans.

Once America entered the war, J.P. Morgan’s loans to the Allies were guaranteed by the US government, making it impossible for his banks to lose money. [124]

After the war, J.P. Morgan was heavily involved in the reparations programmes and was, according to Quigley, the “chief influence” [125] on both the Dawes Plan of 1924 and the Young Plan of 1929.

While J.P. Morgan may appear to be a quite distinct entity from those involved in the British warmongering cartel, Docherty and Macgregor insist that this is not the case.

Investigating the way in which the original family firm had been saved from ruin in 1857 by a massive loan from the Bank of England, where the Rothschilds held “immense sway”, they come to the conclusion that it had become a front company for the Rothschilds. [126]

“It was the perfect front. J.P. Morgan, who posed as an upright Protestant guardian of capitalism, who could trace his family roots to pre-Revolutionary times, acted in the interests of the London Rothschilds and shielded their American profits from the poison of anti-Semitism”. [127]

Having profited from the war itelf, the same financial capitalist circles were also keen to be involved in the subsequent reconstruction.

It has been estimated by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace that the war destroyed more than $400,000,000,000 of property [128] and so more massive loans were required in order to “build back better”.

Years of wild public spending, free of the usual constraints, were good for those lending the money but not for the population as a whole.

Quigley writes: “Since the middle classes of European society, with their bank savings, checking deposits, mortgages, insurance and bond holdings, were the creditor class, they were injured and even ruined by the wartime inflation.

“In Germany, Poland, Hungary, and Russia, where the inflation went so far that the monetary unit became completely valueless by 1924, the middle classes were largely destroyed and their members were driven to desperation”. [129]

After inflation came the crash and depression, The Great Depression as it was perhaps coincidentally labelled, and millions were plunged into unemployment, poverty and starvation.

A Great Theft facilitated by corrupt governments, an enormous transfer of wealth from ordinary people into the already-bulging pockets of a tiny but ruthless ultra-rich ruling class? If that doesn’t sound familiar to you in the 2020s, then you haven’t been paying attention!

While short-term profit was made by supplying the war and medium-term profit came from the payback on various government loans, there was also a long-term element to the plan.

This was to advance, by a giant war-propelled step, the co-ordinated centralization of the dominant clique’s power and control – a process which was to receive a further mighty boost after the Second World War and which is being pushed still further with the Great Reset.

The real nature of the British Empire, later rebranded The Commonwealth, is not generally understood.

Britain was, as Quigley writes, “the center of world finance as well as the center of world commerce” [130] and, in 1914, British overseas investment amounted to some $20 billion. [131]

With larger and larger aggregates of wealth falling into the control of smaller and smaller groups of men, [132] the empire was the vehicle through which financial capitalists could centralize their global economic control.

It was the first phase of what we now call globalisation.

This agenda was successfully pushed forward in various ways during the First World War.

Inside the British government, the warmongering conspirators carried out in 1916 what Docherty and Macgregor describe as “nothing less than a coup, a planned take-over of government by men who sought to impose their own rule rather than seek a mandate from the general public”. [133]

The unelected Milner was appointed directly to the inner-sanctum of Britain’s war planning and Lloyd George “revolutionized government control of production by bringing businessmen into political office”. [134]

Public-private partnerships therefore did not start with Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler, Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair, let alone with Klaus Schwab!

In the USA, President Woodrow Wilson created the US Food Administration and the man placed in control was none other than Hoover, saviour of the starving Belgians and subsequent looter of incriminating documents.

Citing his biographer Lawrence E Gelfand, Docherty and Macgregor describe how Hoover became the “food dictator” [135] and say that he was essentially made “chief-executive of the world’s first multi-national food corporation”. [136]

The post-war period saw a kind of merger of American and British economic interests, they add: “These immense changes represented a long-term financial realignment in favor of Wall Street”. [137]

This was but a step towards a greater aim, which was, as Quigley reminds us, “nothing less than to create a world system of financial control in private hands, able to dominate the political system of each country and the economy of the world as a whole”. [138]

The Federal Reserve Bank having been conjured up in 1913 to enable war funding, the next part of this plan involved the creation of the private Bank for International Settlements in Basle, Switzerland. [139]

Owned by the chief central banks of the world, themselves private corporations, and holding accounts for each of them, the Bank for International Settlements was to serve as “a Central Bankers’ Bank” and allow international payments to be made by merely shifting credits from one country’s account to another on the books of the bank. [140]

At the same time, new institutions were set up to steer and co-ordinate this anglo-american financial imperialism.

The Institute of International Affairs (IIA), also known as Chatham House, was formally established in 1920 and was granted a Royal charter in 1926. It was helped on its way with a gift of £2,000 from Thomas Lamont of J.P. Morgan.

While it pretends to be an independent think tank, Quigley stresses that this is not at all so and warns of the sinister implications of its true function.

“The Milner Group controls the Institute. Once that is established, the picture changes. The influence of Chatham House appears in its true perspective, not as the influence of an autonomous body but as merely one of many instruments in the arsenal of another power.

“When the influence which the Institute wields is combined with that controlled by the Milner Group in other fields – in education, in administration, in newspapers and periodicals – a really terrifying picture begins to emerge…

“The picture is terrifying because such power, whatever the goals at which it may be directed, is too much to be entrusted safely to any group…

“No country that values its safety should allow what the Milner Group acccomplished in Britain – that is, that a small number of men should be able to wield such power in administration and politics, should be given almost complete control over the publication of the documents relating to their actions, should be able to exercise such influence over the avenues of information that create public opinion, and should be able to monopolize so completely the writing and the teaching of the history of their own period”. [141]

Across the Atlantic, a sister organization, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), was created with J.P. Morgan money. [142]

Quigley comments that the Morgan bank has never made any real effort to conceal its position in regard to the Council on Foreign Relations and the published lists of CFR officers and directors “have always been loaded with partners, associates, and employees of J.P. Morgan and Company”. [143]

These moves by financial interests to centralize economic and political power across the world, by means of a network of private institutions, speak of their complete contempt for any kind of real democracy.

But then democracy implies rule by the people, by the majority – if you are a tiny minority determined to flourish by fooling, controlling and exploiting that majority, this is the very last thing you would welcome!

When you nevertheless find it expedient to pretend to support democracy and to pass off your minority control as majority rule, you have created the central and permanent hypocrisy of our contemporary global system.

Another element in the consolidation of the international financiers’ control was the extinguishing of any flames of revolt against their life-destroying industrial slave-system.

Rebellion had been on the rise in the years before the Great War, particularly in German-speaking central Europe, as I wrote a few years back in The Stifled Soul of Humankind.

Free-thinking young people, gathering notably at Ascona in Switzerland, were rejecting the cold machineries of modernity and dreaming of an alternative world based on free communities and harmony with nature. [144]

This was, as I added in 2021, a powerful counterculture, a rebellion against the extinction of life and happiness which was being ruthlessly inflicted by the industrial empire of greed and profit under the false flag of “progress”. [145]

But this blossoming of hope was crushed and buried in the deliberately pre-planned slaughter of the Great War.

Moreover, not just hopes for the future, but connections to the past were blasted into smithereens by the shells and machine-guns on the fields of France.

The war represented a sudden acceleration of “modernisation”, the process by which human beings are torn from all their belonging and turned into helpless and isolated victims of a rapacious system of exploitation.

In wars, says Quigley, “changes which in peacetime might have occurred over decades are brought about in a few years”. [146]

Many old folk customs that had survived the onrush of industrialism stopped for the war and never started up again afterwards. Communities were shattered, traditions abandoned.

It was a different world after 1918: the 20th century New Normal of electricification, telephones, radio, cinemas and urban living.

A local historian here in France told me that the loss of so many young men in the Great War had killed off peasant culture, with the older men and the womenfolk often unable to keep the smallholdings running and forced to seek paid labour in Lyons or Paris.

A step on the road to smart city slavery?

This remodelling of human life to suit the material needs of the industrial system was to be attempted again in Mussolini’s Italy, Hitler’s Germany, Stalin’s Russia and Mao’s China.

In the first year of Mao’s 1958 “Great Leap Forward” (funny how the branding is again so similar!), 90 million peasant women “were relieved of their domestic duties and became available to work for the state”, writes Quigley. [147]

A similar thing happened during and after the Great War in Britain, thanks in part to the Pankhursts’ state-funded campaigning.

This was good news for the money-men. A ruthless employer will pay his workers the lowest wage for which they are prepared to work. If women weren’t the family’s main wage-earner he could get away with paying them less and was thus provided with a handy cheap source of labour.

At the same time, these women were no longer available to perform their previous unwaged work at home and so the family as a whole became yet more dependent on the products of commerce and industry and on the wages required to pay for them.

Communal cohesion, local customs and traditional ways of living have always got in the way of the growth of empires and their centralized control and profiteering.

Imperialists, or globalists if you prefer, have therefore always aimed to rip people up from their roots and throw them into the jaws of their flesh-devouring system.

Our lives and our wishes are of no interest to them.

Docherty and Macgregor write: “By 1912, the Secret Elite had spent over a decade in pursuit of their ultimate aim to create a new world order through the destruction of the old”. [148]

In the same way Klaus Schwab and his accomplices, representatives of the global finance-based dictatorship under which we now so obviously live, welcomed Covid as the destroyer of pre-2020 normality and the great accelerator of everything they have been wanting to foist upon us for years.

Are we really expected to believe that this is all just a Great Coincidence?

V. The future: memory and rage

It has become very clear to me, in the course of researching and preparing this article, that the Great War of 1914-1918 and the Great Reset of the 2020s are related.

They both form part of a series of events intended to trigger a bundle of outcomes beneficial to those organising them, as I have outlined.

The obsessive secrecy displayed by the powers-that-be, the way that they hide their machinations and slander those who threaten to reveal them, confirms the obvious: that these resets, these wars, these great leaps forward, are crimes.

Criminal activity does not always bring social disapproval. Sometimes we can have a sneaky admiration for cheeky rascals who get away with a daring heist or scam.

But these crimes are something else. This is not a question of people robbing a bank, but of banks robbing the people.

Moroever, these robbers are not only prepared to kill in order to grab their booty, but they evidently take a special delight in bloodshed. A massive loss of lives – other people’s lives, the little people’s lives – seems to be a treasured feature of their great historical showpieces.

These are psychopaths, twisted mass murderers who take a sadistic pleasure from the piles of corpses they leave behind them.

Their vision of the future is that of the cruel ruling clique depicted by George Orwell in his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four: “a boot stamping on a human face – for ever”. [149]

Each “Great” event in their infernal historical series is another stamping of that boot of power and greed on to our collective human face.

So how can we stop them? How can we reassure young Willie McBride that it will not all continue to happen “again and again and again and again”?

The circles behind the Great War and the Great Reset have such loathsome and malign intentions that they can effectively be described as evil. Against this dark force, we therefore need to channel the light, as I have written before.

We also need to enshrine and radiate all that we love about the life that they want to steal from us: our belonging to nature, our friendships, our local traditions, our romances, our dreams, our sense of joy at being ourselves, in our own bodies, in our own commmunities.

But I am not sure that this positive energy, necessary though it is, will be enough.

The ruling clique has been perfecting its grip on power for a very long time now. In the world it has carefully constructed, where all real value has been replaced by the reign of ill-gained money, it has the physical means to ensure its domination endures.

To break through the system’s defensive barriers we need to arm ourselves with an energetic battering ram of such strength that nothing they try to do will stop it.

And where could we source that from?

At the start of this essay, I wrote about the way in which I have always felt bound in grief with the victims of the Great War and how I feel the memory of their suffering is part of our collective unconscious.

I think that now is the time to use that memory, to access that deep hurt to our collective psyche and turn it into the momentum we need to bring down this odious system.

You could see it, if you like, as calling on the ghosts of the war dead to rise up and march on the gold-plated citadels of the power that slaughtered them.

Millions and millions of phantoms, joined by millions more victims of the same power’s violence and exploitation across its vast putrid empire, will advance silently towards their murderers.

Their physical form will be you and me, the bodily incarnation of humankind today, but their spiritual essence will be age-old and angry.

Imbued with our knowledge of all that has been done to us, and our determination that it must never happen again, we and those who came before us will together tear down the oppressors’ prison camps and counting houses so as to clear the path for a free and joyful human future.

This essay should ideally be read in conjunction with A developing evil: the malignant historical force behind the Great Reset

NOTES

[1] Carroll Quigley, Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time (Reprint, New Millennium Edition, New York: Macmillan, 1966), p. 161.

[2] Gerry Docherty and Jim Macgregor, Hidden History: The Secret Origins of the First World War (Edinburgh & London: Mainstream Publishing, 2013), p. 12.

[3] Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, p. 602.

[4] Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, pp. 82-83.

[5] W.T. Stead, The Last Will and Testament of Cecil John Rhodes, p. 55, cit. Jim Macgregor and Gerry Docherty, Prolonging the Agony: How the Anglo-American Establishment Deliberately Extended WWI by Three-and-a-Half Years (Walterville, OR: Trine Day, 2018), p. 5.

[6] Docherty and Macgregor, Hidden History, p. 31.

[7] Carroll Quigley, The Anglo-American Establishment: From Rhodes to Cliveden (Dauphin Publications Inc, 2013), p. 135.

[8] Quigley, The Anglo-American Establishment, p. 38.

[9] Docherty and Macgregor, Hidden History, p. 366.

[10] Macgregor and Docherty, Prolonging the Agony, p. 6.

[11] Niall Ferguson, The House of Rothschild: The World’s Banker 1849-1999 (New York: Penguin, 2000), p. 285.

[12] cit. Ferguson, p. 441.

[13] Docherty and Macgregor, Hidden History, p. 18.

[14] Quigley, Tragedy and Hope, pp. 602-03.

[15] J. Lee Thompson, Forgotten Patriot (New Jersey: Rosemount Publishing, 2007), p. 75, cit. Docherty and Macgregor, Hidden History, p. 27.

[16] Quigley, The Anglo-American Establishment, p. 86.

[17] Docherty and Macgregor, Hidden History, p. 53.

[18] Bruce Lockhart, Memoirs of a British Agent, p. 206. cit Macgregor and Docherty, Prolonging the Agony, p. 469.

[19] Paul Cudenec, Fascism Rebranded; Exposing the Great Reset: Winter Oak, e-book, 2021, pp. 280-284.