A call to preserve wanderlust and push back against the 21st century digital prison

For centuries, the freedom to move has been inextricably linked to the open road. The imagery of the open road has been ingrained into the American mythos. Nothing is more alluring — more potent. Some of the greatest thinkers wrote fondly about the open road and all that it brings, including Walt Whitman who penned the poem ‘Song of the Open Road’ in 1856.

Whitman opens with the following lines,

“Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road,

Healthy, free, the world before me,

The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.”

To Whitman — and to the American mythos — the open road is a space for growth, new beginnings, and rebirth. And it’s represented everywhere — in literature, media, advertisements. Jack Kerouac reminds us to value the present moment in On the Road; In The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck invites us to follow the journey of the Joad family from their Oklahoma home to California; Hunter S. Thompson brings us along on a drug-fuelled journey to Las Vegas. In advertising, we are bombarded with car commercials, and now governments and automakers are furiously racing to build the latest and greatest electric vehicles, a new kind of vehicle that would allow us to venture out into the open road without the added guilt of contributing to emissions.

The open road does not discriminate — rich or poor, young or old — it is open to all who seek new experiences, commune with nature and people, and venture beyond one’s comfort zone.

More importantly, the promise of the open road speaks to our primal need to move freely between spaces.

By contrast, indoor spaces are stifling and soulless — they keep us bound up in space and time, immobile, and unchanging — at least according to Whitman.

He writes,

“You must not stay sleeping and dallying there in the house, though you built it, or though it has been built for you. . . Inside of dresses and ornaments, inside of those wash’d and trimm’d faces; Behold a secret silent loathing and despair.”

While the car is closely intertwined with the mythos of the open road, it’s not a required component. The car is simply a tool — an instrument towards freedom of mobility. It is both a material item that helps free us, but it also serves as a symbol of Western values and how we value certain personal freedoms, particularly the freedom to move — a freedom that has been literally woven into our cultural, social, political, and legal fabric. It is, by all accounts, one of the most cherished freedoms we have.

The Rise of Anti-Freedom Sentiment

But in recent years we’ve been told, in various ways, this freedom, among other fundamental freedoms, is not so desirable after all. We’re told it’s because of American car culture, and climate change, and convenience, and sustainability, and safety, and public health — all of these reasons and more are constantly thrown our way as a justification to remain digitally tethered and physically caged in hyper-dense spaces, which is, we are assured, a Very Good Idea and one that we should unquestioningly support lest we risk being labelled a climate terrorist, or an oil industry shill, or a conspiracy theorist, or any other absurd label used to discredit any opposition.

This anti-freedom sentiment didn’t come out of nowhere.

Culturally it has been simmering for some time, and finally, it was Covid that helped tipped the scales towards popularizing this perception that freedom is not a value worth preserving. At one point we held these fundamental freedoms so dear to us, but the ruling elite has successfully led us to believe that a pro-freedom stance is somehow rooted in dangerous ideology, like far-right extremism.

There are a few key events in history that helped set the conditions for the rising popularity of this sentiment encouraged by contemporary urban planners and techno-utopians alike, including the rise of consumer culture, marked increase in surveillance technology, normalization of ‘lockdowns’ as a lifestyle, and the rise of New Urbanism.

1950s: Setting the Roots of Convenience Culture

The post-WWII era saw a great leap in technological progress. The 1950s was revolutionary for convenience technology: processed foods were marketed towards housewives as a way to give women more freedom; household appliances like the dishwasher, microwave, washer and dryer were popularized to reduce time spent doing housework; and food preservation products like Saran Wrap and Tupperware allowed families to store leftovers, further freeing up more time for the modern housewife.

Consumerism took off and women were happily purchasing more convenience products they were promised would help free up their time otherwise spent tending to the household.

In a few short decades, the culture of convenience, fuelled by technology and sold as ‘progress’, mutated into something unrecognizable. We have entered an era of convenience on steroids in which everything can be delivered to us with the tap of a button: food, medication, Starbucks coffee, toilet paper — completely eliminating the need to leave the house at all. In 2021, Uber Eats saw a 72% increase in revenue, generating $8.3 billion, with the largest consumer base comprising of 25 to 34 year olds. Amazon Prime doubled its user base in just a few years, going from 100 million in 2018 to 200 million in 2022. Since 2020, Zoom’s quarterly revenue grew by almost 600% — and this trend is expected to persist. A 2022 Pew survey found that 35% of respondents placed socializing and going out as a lesser priority. From the survey, one respondent said, “Being social in large crowds is less important now. It’s less important to go out.”

Another said,

“I stay at home more, avoid crowds and public spaces. I also shop earlier to avoid people, buy more in bulk so I don’t have to go out as often.”

More people report to have more online friends than ever, but zero real life friends. Who needs friends in this new world anyway? Just hop online. All of our activities are being mediated through a screen, and Covid has simply normalized this.

It’s never been easier to remain static and fixed to one space, both physically and psychologically, and this transforms everything from our relationships, to how we communicate, how society is structured, and how we coexist in this techno dystopian world. The most worrying part of this trend is that many people seem to embrace it.

Vehicle Surveillance Technology: 1980s to Today

Fast forward to the 1980s.

In the early 80s, vehicles were assigned unique serial numbers in which to identify them; electronic toll systems closely followed. In the early aughts, vehicles came equipped with black boxes, then 9/11 happened and the streets themselves became encumbered by surveillance technology — including CCTV cameras, which became the norm around the world. Now they’re as much as a part of the landscape as street signs and traffic lights. Today we have smart vehicles that collect a wide array of information about the driver, including location data, charging habits, start and end times of journeys — it even captures details like how much air conditioning has been used. You would think people would be cautious of this, but many drivers are willingly sharing this data with others because analyzing driving metrics is apparently a fun hobby for techno optimists.

In the era of Big Data, this information is invaluable, and it can very easily be used to regulate human behaviour. It’s already happening. Volkswagen’s loyalty app Boneo allows drivers to collect points for completing daily tasks and challenges. Drivers can redeem their collected points for various things, like a free car wash, free car service, and even concert tickets.

Volkswagen posted this video attempting to sell its ‘loyalty’ program:

The gamification of driving is well underway, and few seem to be concerned of its effects. But I don’t see this technology as being innocuous. Quite the opposite. Gamification is a conditioning tool used to further reduce humans to lab rats, it directly manipulates human behaviour and limits our agency. It is inherently dehumanizing as it uses external triggers (i.e., technology) to modify our behaviour. As a result, there is little to no conscious independent decision making involved.

The vehicle quickly became a leash that tethered, and limited us, taking on a life of its own and removing our agency completely. These technology trends are the anti-thesis of what the open road symbolizes. Electric vehicles would sound the death knell of the freedom that the open road brings (and they also happen to be incredibly resource-intensive and impractical).

The Freedom to Move — a freedom that was once deemed essential to the cultural zeitgeist — became an afterthought. The allure of convenience, comfort, and safety have successfully transformed our society for the worse.

Normalizing ‘Lockdown’ as a Way of Life

Covid, being the global disruptor that it was, normalized the concept of ‘lockdowns’ and this continues to have residual impact globally. Before Covid, the concept of lockdowns was hardly ever used in a public health context. In prior outbreaks, public health officials always expressed reluctance to lockdown society. It was only ever done in selective settings, like care homes. But with Covid, a new precedent was created. Western societies realized they, too, could implement oppressive measures that would limit freedom of movement and that people would, by and large, not only comply, but be cheerleaders for their government, and even snitch on their neighbours if given the opportunity.

Now people are eager to spend every waking moment inside, with some even still self-isolating to this day for fear of getting infected, while others — who do spend time outside —have concocted more ways in which they could separate themselves from the outside world — they refuse to breath the open air, touch the natural world with their fingers, or even communicate with others without self-imposing barriers made out of rubber, latex, and plastic.

No longer are agoraphobic tendencies relegated to those with mental disorders, this mentality has seeped into the general public and become the default state of being, not an anomaly.

A Stunted Society in the Digital Age

Today, the open road no longer feels freeing, but daunting.

Exploration became synonymous with uncertainty, and uncertainty is increasingly met with resistance and anxiety. For a long time, the open road was associated with the popular rite of passage among young adults in Western society: getting your driver’s license. It is only in recent years that teenagers are doing away with this rite of passage entirely. Teenagers are proving that the open road only leads to more anxiety. Kids aren’t driving much anymore, and while climate activists seem to celebrate this, this phenomenon is indicative of deeper psychological issues. Kids aren’t just getting their driver’s licenses, they’re not leaving their homes at all. They’re socializing less in person, engaging in fewer ‘riskier’ activities, dating less, and so on.

All of this comes at the cost of our livelihood, our raison d’etre. This is the lifestyle that is being pushed by the ruling class, and many are applauding it. Many tech critics have long warned of the consequences, but governments, tech companies, and profit-driven corporations are hurling us ever closer to tech dystopia, and it feels more suffocating by the day.

The Case Against the 15-Minute City

City planners are taking advantage of all of these coalescing trends by way of promoting New Urbanism, an architectural movement that is focused on pushing back against faceless, developer-driven suburban spaces. By extension, they are promoting the controversial 15-minute city, described by supporters as a resistance movement to concrete, car-driven spaces that were popularized in the 1960s. Decades ago, organically connected communities were stripped away to make room for faceless, sterile gentrified residential and commercial developments.

At first glance, the 15-minute city model sounds like a worthy cause — and it’s making headway all around the world.

But it comes at a great price.

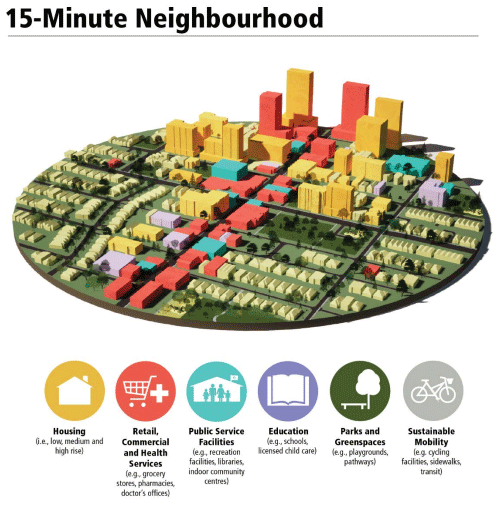

The 15-minute city, coined by urban planner Carlos Moreno, focuses on creating a walkable, dense, mixed-use space that has all the residents’ necessary amenities nearby. The idea is that residents would be able to access all of their daily needs (food, housing, work, education, culture, etc.) all within a walkable distance, eliminating the need for a vehicle entirely.

In 2016, Moreno elaborated on what he thinks the 15-minute city might look like in an oft-cited paper, ‘Introducing the “15-Minute City”: Sustainability, Resilience and Place Identity in Future Post-Pandemic Cities’.

But the 15-minute city isn’t an example of New Urbanism — it’s a perversion of it.

Unlike how urban neighbourhoods were pre-1960s, the 15-minute city would not be a ground-up decentralized network. The 15-minute city is just the latest example of top-down, developer-driven urban planning that appears to put the needs of the residents at the forefront, but the decisions are still being made behind closed doors by city officials, developers, and tech companies who value profits above all else.

The paper proposes a number of technologies to implement including Blockchain technology and cashless transactions . The authors even encourage more ways to “communicate virtually” so you would never have to leave your home again. These measures are expected to say in the “post-pandemic” society, though I doubt any of these measures would contribute to a close-knit, inclusive, interconnected community.

Some questions arise: Will there be quotas installed? Will residents have to seek permission to leave the 15-minute neighbourhood? How will their data be used (depending on what digitals tools are in place)? Will residents be further taxed? Will residents be required to ‘opt-in’? These questions aren’t hyperbole. As of this writing, Oxford City Council is implementing what it calls ‘filters’ to limit how many times a year residential vehicles can pass through. If any of the residents drive outside their district more than 100 days of the year, they risk being fined £70. This isn’t a conspiracy ; this is happening in real time. In an attempt to combat ‘misinformation’ and pushback against ‘conspiracy theories,’ Oxford City Council released FAQs that clarified that the traffic filters would not be physical barriers, but rather they would install traffic cameras that can read number plates — which is worse because it creates the illusion of freedom. The absence of a physical barrier does not make us free if there are omnipotent digital tools in place that have the express purpose of monitoring our movements. It’s this type of soft cage surveillance that is the most insidious and misleading.

What part of any of this would allow for more organic ways of building cohesive, inclusive, and dynamic communities? I suspect Jane Jacobs, an activist who worked hard to pushback against urban sprawl and who leaves behind a legacy that continues to influence urban studies to this day, wouldn’t be enthused about the 15-minute city, either. Jacobs wanted to nurture tight-knit, vibrant communities, not create communities devoid of humanity and community interaction altogether.

In this article, the writer says ‘15-minute’ neighbourhoods did exist at one point, but this was 60 plus years ago. Today’s 15-minute city isn’t trying to replicate what we had before, it’s trying to create a new type of way of living never seen before. This proposed way of living demands scrutiny.

In the same article, the writer naively believes that critics of digital monitoring tools have no argument to stand on, but history is littered with examples demonstrating otherwise.

Unfortunately, the mainstream media has already solidified their narrative, propping up this model, while calling anyone who criticizes it a ‘conspiracy theorist.’ For example, articles like this one, “The case for 15-minute cities” and this one, “The ‘15-minute city’ backlash is part of the great climate change conspiracy theory,” associate any pushback to the 15-minute city as a ‘conspiracy theory,’ effectively creating an echo chamber and sound bytes that are bound to be reused over and over again in the months and years to follow.

Paving the Way Toward the Smart City

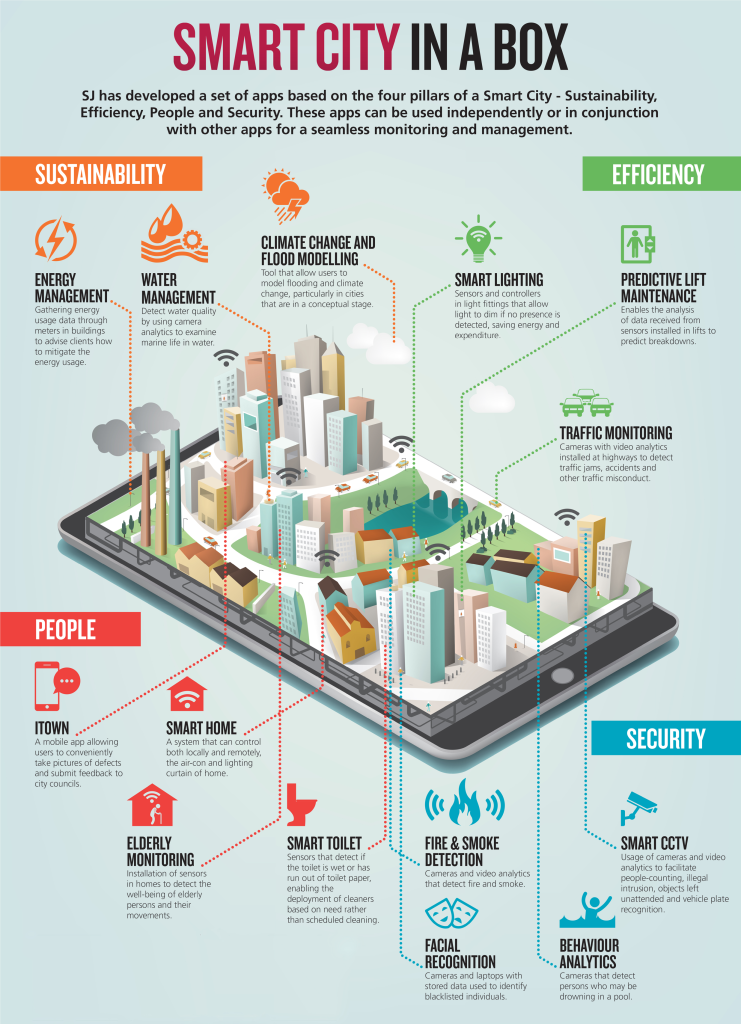

But there’s more to it. The 15-minute city opens the doors to something more insidious: the Smart City.

Moreno’s paper on the 15-minute city has an entire section dedicated to explaining the model of the ‘Smart City’ and what this might look like against the backdrop of a “post-pandemic” world, though the two are basically interchangeable concepts at this point.

Using the excuse of Covid and climate ‘lockdowns’, the paper’s authors believe urban spaces need more alternative and ‘sustainable’ ways of living that would better help residents observe health protocols in the case of a pandemic.

One of the key components of the Smart City is the use of digital technologies to optimize daily life. The authors note that that IoT (Internet of Things) devices which collect and send data to a centralized network, where the data would be then analyzed and shared in real-time.

The authors write,

“The availability of IoT devices, which . . . will be in excess of over 75 billion devices by 2025, coupled with technologies such as Artificial intelligence (AI), Big Data, Machine Learning and Crowd Computing and others is expected to actualize the proposed 15-Minute City concept.”

The Smart City is being pushed by governments all around the world. For example, the Canadian government rolled out a ‘Smart Cities Challenge‘ which awarded millions of dollars in funding to cities who were willing to implement their own smart city. Montreal, Quebec nabbed the top spot and was awarded $50 million.

Moreno notes the goal of smart technology is to address “challenges like increasing energy demand, traffic issues, social inequality in housing and in provision of services like health, improve economic status of residents and confront the challenge of sustainability heads-on.”

Some examples of the digital tools that could be used are optimizing online shopping, bike sharing, and even implementing drone delivery services (brought to you by Amazon), noted by the paper’s authors.

The entire purpose is to eliminate the need to travel, as noted by the authors. It must be emphasized that cities all around the world are already establishing rules on how often and how far residents of a 15-minute city can travel (See: the Oxford example mentioned above).

International agencies are also deeply invested in neo-techno-urbanism, including the WHO, UN-Habitat, and OECD. They also happen to be the same agencies behind pushing towards the centralization and regulation of society by means of digitization, whether it be universal digital currency or universal digital IDs — the point is these digital tools must be scalable, adaptable, and universal. Of course, privacy and security questions arise. Who will have access to this data? Will it be shared with third parties? How will the data be used? How long will this data be kept? How will government officials use these apps to surveil, control, and influence human behaviour? We have seen all of this happen before — again and again. History is littered with examples of how our data has been used to control and surveil residents, dating back to the 1800s. For a detailed account of the history of surveillance, I recommend Christian Parenti’s book The Soft Cage (2004), which goes into great detail of how surveillance technology and how its primary use has been to control populations from the past to the present day.

A Digital Prison of our Choosing

When you pull back the euphemisms and buzzwords, the Smart City is comparable to a digital prison in which the sole goal is to make it as as easy as possible to remain imprisoned, fixed, unmoved. But it’s being sold under the banner of ‘safety’ and ‘convenience’ — and people, on the whole, happily embrace this new form of enslavement.

Like Walt Whitman’s critique of indoor spaces, I fail to see how anyone can live a full, rich life if they are primarily motivated by convenience brought to them via digital tools. Indeed, I suspect mental illness, substance abuse, and other issues will be more commonplace in the years to come with people not understanding why they feel the way they do if they have everything they could ever need right at their fingertips, Wall-E style (which is much too optimistic of a dystopian even by today’s standards).

Our best defence against the 15-minute city is to continue advocating for our fundamental freedoms, demonstrate that critics of these models don’t come from ‘conspiracy theorists’ but by ordinary citizens who value their autonomy and who want to preserve their humanity. The concept of the open road has remained a mainstay in North American culture for centuries for good reason— at our core, we crave adventure, journeying outward, embracing the unknown, and meeting others along the way. This is how we will move forward and keep our humanity — something that could never be replicated or replaced by AI or apps. There’s no greater feeling than hitting the open road and journeying into the unknown. This is something that must be preserved for the sake of humanity.

For additional reading, I recommend checking out Nowick Gray’s article on the Short History of Freedom for a concise summary of fundamental freedoms described by David Graeber and David Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (2021).

Feature Image credit: Rene Magritte – The False Mirror [1928] (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)